As part of the John Locke Foundation’s NC250: Freedom’s Vanguard initiative, this essay contest invited students, scholars, historians, and writers to explore North Carolina’s pivotal role in the American Revolution and the founding of the United States. The project highlights the state’s contributions to independence, liberty, and the shaping of the American Republic.

In Halifax, North Carolina, stands a yellow painted tavern adorned with a sign bearing an eagle and shield. Exhibit panels fill the rooms of the first floor discussing life within the Colony of North Carolina and history of taverns; located within a corner of a room is a single plaque with a scan of a diary entry, a transcription of its page, and a paragraph with the line “George Washington spent two nights in Halifax.” Hundreds of buildings across the Eastern United States claim connections to Washington and do so with the infamous phrase “George Washington slept here.” What began as a line to bring in tourists evolved into a tool for preservation, resulting in the saving of numerous historic sites and buildings connected to the nation’s revolutionary legacy. North Carolina’s relationship to this phrase, however, does not follow the norm for Washington-connected places, but instead tells a history of a one man’s journey to tour the places where North Carolinians debated and fought for our Revolution.

Each state has its own history with the line “George Washington slept here”: Virginia was Washington’s home, New Jersey and New York were places he fought, and Pennsylvania was where he sat as our first president. On the other hand, North Carolina is unique compared to those farther north; Washington never lived in North Carolina, never had a headquarters in a mansion here, and never fought in any revolutionary battles here. Instead, in 1791, Washington toured the southern states and visited the sites where North Carolina founders lived, where the first official call for independence was penned, and walked the hallowed ground where Carolina patriots fought. This paper discusses North Carolina’s early preservation movement and Washington’s 1791 Southern Tour, including the places he visited, some of which remain sites connected to North Carolina’s Colonial and Revolutionary legacy.

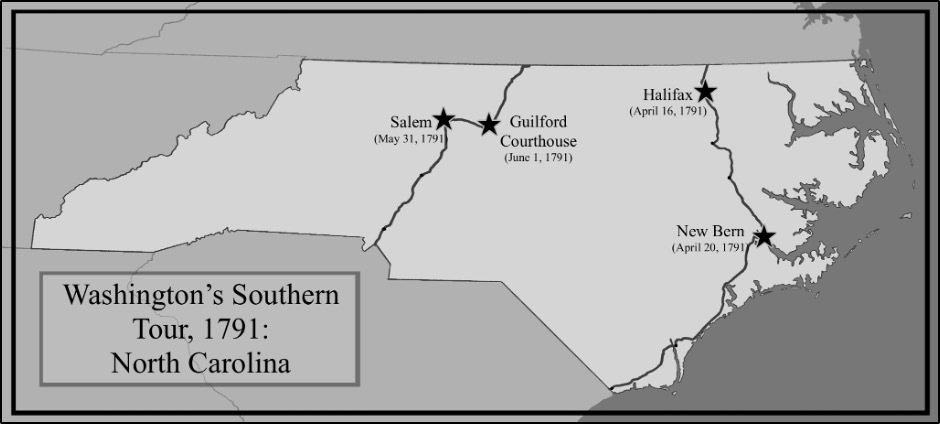

This paper begins with Washington’s 1791 tour of the southern states, focusing specifically on the North Carolina leg of his trip from Halifax to Wilmington and from Salem to the battlegrounds of Guilford Courthouse. Afterwards, the paper traces the history of the line “George Washington slept here” from the 1830s into early historic preservation projects, such as Mount Vernon, Morristown, and Valley Forge, and discusses its meaning in the present day. Honing in on North Carolina, the paper discusses the state’s preservation history beginning with Guilford Courthouse in 1889 and early associations formed to protect and save historic buildings. Following the historic preservation movement within North Carolina, this paper focuses on four buildings that have at one point claimed or continue to claim a connection to Washington: the recreation of Tryon Palace and preservation of John Wright Stanly House in New Bern, Salem Tavern in Salem, and lastly, the Eagle Tavern in Halifax.

George Washington’s southern tour, 1791

In 1789, during his first term as president, Washington embarked on a journey to tour every region of the United States. Unfortunately, due to the duties of the presidential office, he was only able to complete his tour of the northern states. It was not until 1791 that Washington was able to coordinate his trek through the southern states. On March 21, 1791, Washington and his caravan set off from Philadelphia, crossing through Delaware, Maryland, and into Virginia. Washington had only visited North Carolina once before, in 1763 while exploring the Great Dismal Swamp, and his tour of the southern states marked his first and only time in South Carolina and Georgia.[1]

On April 16, 1791, Washington set out from Petersburg, Virginia, and crossed into North Carolina. After setting off, the goal was to locate lodgings between Petersburg and Halifax; unfortunately, the group was unable to locate decent lodging and chose to travel forty-eight miles down to Halifax. The city of Halifax was the scene of one of the most important events in the lead-up to the American Revolution. A few months prior to the signing of the Declaration of Independence, in April 1776, the representatives of the Colony of North Carolina gathered in Halifax and penned the Halifax Resolves, which became the first document to call for independence from Great Britain. Despite its importance in history, the town had lost most of its popularity by 1791. When Washington arrived in Halifax, he noticed its declining numbers, writing that “[i]t seems to be in a decline, & does not, it is said, contain a thousand souls.”[1] The following day, April 17, Washington wrote of having dined with several gentlemen in the town. During the two nights that he stayed in Halifax, he lodged at a tavern in town. Washington was well known for keeping details notes in his diaries; however, he made no mention of which Halifax tavern he slept in.

Washington left Halifax on April 18 and lodged at Tarboro for the night, and on April 19, they traveled farther south and dined in Greenville. On Wednesday, April 20, the group arrived in New Bern, previously North Carolina’s colonial capital, which was also in decline due to the state’s new capital of Raleigh being formed farther inland. During his time in New Bern, Washington spent two nights in the John Wright Stanly House, and on the evening of April 21, he dined and danced with citizens in the Tryon Palace, formerly the home of the colonial governor.[2] In his diary, he described the palace as “a good brick building but now hastening to ruins,” an observation that became true only a few years later when a fire demolished the palace.[3]

On April 24, the caravan reached Wilmington, its final stop in North Carolina before crossing into South Carolina. Back in January 1781, a group of British forces occupied the city of Wilmington to set up a base of operations for the invasion of North Carolina by Lord Cornwallis.[4] Cornwallis was rumored to have made his headquarters in the home of local loyalist John Burgwin, whose house is now known as the Burgwin-Wright House. After the British victory at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in March 1781, Cornwallis and his forces marched back to Wilmington to resupply before later setting off north to Yorktown.[5] It is unknown if, during Washington’s visit to Wilmington, amidst the dining and dancing, he reflected on this connection to Cornwallis and the victory he won years prior at Yorktown.

After leaving Wilmington, Washington and his group traveled through South Carolina, making a stop at Charleston, before proceeding down to Savannah, Georgia. From Savannah, they head inland and came back up into North Carolina. On May 31, they reached the village of Salem, “a small but near Village … having with itself all kinds of artizens [sic].”[6] The following day, Wednesday, June 1, Washington toured the village, writing he “[s]pent the forenoon in visiting the Shops of the different Trades Men… and their place of worship.”[7] After two nights in Salem at the Salem Tavern, Washington and his caravan, along with the North Carolina Governor Alexander Martin, traveled up to Guilford. Along their way, they stopped at the battlegrounds of Guilford Courthouse. There, Washington reflected on the battle, writing “I examined the ground on the Action between Generals Green [sic] and Lord Cornwallis commenced.”[8] Lastly, on Saturday, June 4, Washington and his group crossed what William Byrd described as “the dividing line betwixt Virginia and North Carolina” and continued their journey in Washington’s familiar home state of Virginia.[9] Following his southern tour, Washington would never visit the Carolinas or Georgia again, but the memory of his few weeks within those states left enough of an impact to have the line “George Washington slept here” placed on a few colonial houses.

George Washington slept here

The history of the infamous quote “George Washington slept here” oddly begins during a national financial crisis. In the late 1830s, the United States was hit by a major recession known as the Panic of 1837, resulting in banks collapsing, rising prices, and financial ruin for business owners, merchants, and farmers. One such farmer was Jonathan Hasbrouck III in Newburgh, New York, who in 1837 was forced to mortgage his house, an 18th-century, Dutch-style farmhouse overlooking the Hudson River. Short on funds, Hasbrouck decided to use the property’s history to raise money, and in 1838, he began promoting the house’s connection to George Washington.[1] From April 1782 to August 1783, as the American Revolution drew to a close, Washington called the Hasbrouck house his headquarters. Selling tours of Washington’s former headquarters, Hasbrouck was able to pay for the house’s upkeep and maintenance, and likely unbeknownst to Hasbrouck, he had opened the first proto-house museum in the country. In 1850, the State of New York purchased the house and property, opening it later that same year as the nation’s first publicly owned historic site and the first house museum in the United States.[2]

By 1853, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA) was founded to restore and preserve George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon, creating the first nationwide historic preservation movement. The MVLA’s efforts soon inspired numerous groups to save other places linked to Washington. In 1874, the Washington Association of New Jersey (WANJ) was founded and acquired Washington’s Headquarters at the Jacob Ford Mansion, and in 1933, the association donated the property to the National Park Service (NPS), becoming the first National Historical Park, today known as Morristown National Historical Park.[3] In July 1878, the Centennial and Memorial Association was formed with the goal of purchasing land at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and preserving the headquarters of Washington, today also part of the NPS as the Valley Forge National Historical Park.[4]In the decades that followed, historical societies and associations were formed to save these Washington connected buildings — Mary Washington House (the home of Washington’s mother) in Frederickburg, Virginia, in 1890, Fraunces Tavern in New York City in the 1890s, Trumbulls War Office in Connecticut in 1891, and Haywood-Washington House in Charleston (the first house museum in South Carolina) in 1929, to name a few.

According to Washington historian, Edward G. Lengel, in Inventing George Washington: America’s Founder, in Myth and Memory, “[b]y 1911, the ‘Washington slept here’ phenomenon had become a standing national joke.”[5] Locals along the Eastern United States saw tourists coming with an interest in the founding father, and with their lack of knowledge, innkeepers and homeowners began putting signs out front claiming “George Washington Slept Here.” Despite Lengel identifying the phrase as a “national joke” by the 1910s, the claim continued on; however, many people across the nation had become aware of the cliché, as a newspaper articles from 1939 reported “[a]lmost every house between Frederick (Maryland) and Washington has a little sign in front of it reading: ‘George Washington slept here.’ George must have been what is known as an inveterate snoozer. When he did his work is your guess as well as ours.”[6]

While private homes and inns were still using the phrase to attract tourists and business, historical societies and associations connected to actual places associated with Washington, seeing the distrust the line was bringing, began rewording their connection to Washington. The Historic Markers Database is an online database where users record historic markers around the world; studying over 200 signs and plaques photographed for the site reveals historical societies’ interest in disconnecting from the line, “George Washington slept here.” Historic markers erected between the late 1920s to the 1930s illustrate a dramatic erasure of the word “slept” from their discussion of Washington. Instead, the word “slept” was substituted with “lodged,” “rested,” or “occupied,” and in some cases “stayed overnight.” Others focused specifically on what he was doing there, rewording the phase to “dined here,” “stopped here,” or “was entertained here,” with a few markers quoting lines directly from Washington’s diaries, “Din’d and Lodg’d at …,” as a way to further confirm their connection.[7] During this time, North Carolina’s State Historical Commission had a series of markers erected for places Washington visited during the southern tour; these were placed out front of historic buildings such as the Eagle Tavern in Halifax and on roads outside towns such as Tarboro and Salem.

While it’s difficult to know how much this rewording helped to encourage a sense of truth for passing tourists, the line remains both a popular tourist attraction and a cliche. On tours of 18th-century houses, tourists will still look down at the wood floors in awe as a tour guide announces, “Washington stood on these floors!”, or will make a soft but disappointed sigh when the docent explains, “Sadly, Washington never actually even visited here.” Today, this interest in Washington remains, and its impact can be seen woven throughout the early preservation movement.

Early preservation in North Carolina

North Carolina’s first step into saving historic sites occurred in 1887, when the Guilford Battle Ground Company began preserving land associated with the Battle of Guilford Courthouse.[1] By 1896, the Roanoke Colony Memorial Association, a nonprofit group, purchased the site of Fort Raleigh, the first English settlement in America. In 1903, the General Assembly founded the North Carolina Historical Commission, and in 1907, the commission was charged with the “preservation of battlefields, houses, and other places celebrated in the history of the state,” resulting in the preservation of military sites such as Guilford and Moores Creek Bridge.[2] While lands associated with historic events were being purchased during North Carolina’s early preservation movement, it was not until the late 1910s and 1920s that buildings began to enter the movement. In 1918, the Cupola House in Edenton became the first “community-wide effort in North Carolina to preserve a historic structure” as residents rallied to save the 1758 house.[3]

National organizations moved into saving North Carolina’s historic buildings, with the Society of Colonial Dames of America of North Carolina purchasing the Joel Lane House in 1927, whose plantation became the site for the state’s capital of Raleigh in 1792. Later in 1937, the Colonial Dames purchased the circa-1770 Burgwin-Wright House in Wilmington, which promoted its preservation as the headquarters of Cornwallis and which today remains a house museum.[4] Along with the Colonial Dames, the Daughters of the American Revolution began purchasing historic properties in the state. During the 1920s, the North Carolina Daughters of the American Revolution attempted to purchase the remaining wing of Tryon Palace in New Bern. While unsuccessful in acquiring the building, New Bern’s colonial palace became a statewide topic of interest.

Around this time, in Virginia, Rockefeller’s massive recreation of the colonial capital at Williamsburg had preservationists across the country watching, and North Carolinians inspired by Rockefeller chose New Bern as their Colonial Williamsburg project. New Bern’s restoration of the colony capital included the reconstruction of the governor’s palace as its main goal; however, the first building restored in New Bern was the John Wright Stanly House in 1935, where in 1791 “Washington spent two nights in the house.”[5] As other communities across the East Coast were saving historic buildings and battlefields, in 1931, Charleston, South Carolina, led the way with zoning historic districts to prevent modern development. The following decade, in 1948, Winston-Salem adopted North Carolina’s first local preservation ordinance, helping protect the historic 18th-century village of Salem. In the years that followed, the colonial cities of Halifax, Edenton, New Bern, and others were designated historic districts. Today, these places remain standing because of the effort put in by North Carolinians interested in their state’s history; within these stories of preservation is an underlying desire to connect with Washington and the larger history of the nation.

Tryon Palace recreation, New Bern

Despite North Carolina having the first English settlement with the Colony of Roanoke, it was not until the 1760s that North Carolina had its first permanent colonial capital. The colony had several temporary capitals until it was finally decided to construct a permanent location along the Neuse River, in the town of New Bern. Between 1767 to 1770, Tryon Palace was constructed as the colony’s capital and home for the Royal Governor. The palace was designed by John Hawk, an English architect who arrived in the colony in 1764 with Governor William Tryon. Completed in 1770, Hawk designed one of the finest public buildings in colonial North Carolina. Designed in the Georgian style, the Tryon Palace was perfectly symmetrical and included a large, free-standing, walnut stairway at its center illuminated by a skylight in the ceiling. However, despite the grandeur of the palace, Governor Tryon and his family only resided in the house for a year before Tryon was appointed to the governorship of New York in 1771. The second royal governor to live in the palace was Josiah Martin, who was also the last royal governor to call Tryon Palace home, as in May 1775 he fled New Bern at the start of the American Revolution. American patriots continued to use the building as the capital until 1792, when the capital moved to Raleigh.[1]

During Washington’s 1791 Southern tour, the Tryon Palace hosted a dinner and dance in his honor. In his diary, Washington wrote on “Thursday 21st [of April]. Dined with the Citizens at a public dinner given by them; & went to a dancing assembly in the evening—both of which was at what they call the Pallace [sic]—formerly the government House & a good brick building but now hastening to ruins.”[2] As Washington had noted, the palace was falling into ruins, and after the capital fully transitioned to Raleigh, the palace lost its primary purpose and was converted for various uses, such as a Masonic lodge and a boarding house. In February 1798, a fire started in the palace’s cellar where hay was stored, the flames burned through the floor, reaching the free-standing stairway at the center of the building. The symmetrical form of the Georgian palace, originally designed to reflect balance and order, had accidentally created the perfect inferno, fueled by the walnut staircase, oxygen was pulled from the various doorwalls branching off the central stairwell, and creating a flame that shattered the glass skylight. The flames quickly devoured the palace from the inside, with only the kitchen and stable offices surviving the devastation.[3]

By the 19th century, only the Kitchen Office remained as George Street had been extended over the Tryon Palace’s foundation, connecting to a bridge crossing over the Trent River. With news of Rockefeller’s recreation of Virginia’s colonial capital of Williamsburg, a movement began in the 1930s to restore North Carolina’s colonial capital. Funds were raised in the early 1930s with a portion used for the preservation of the Stanly House.[1] It was not until 1945 that the Tryon Palace Commission was created and charged with the reconstruction of the palace using Hawks’ original plans and building on the original foundation. To achieve this, 50 buildings had to be removed that were located on the original palace grounds, and the extant George Street (part of Route 70) had to be rerouted. Afterwards, archaeologists were able to locate the palace’s foundation on which the reconstruction was built. In 1959, the Tryon Palace was opened to visitors as “North Carolina’s first great public history project.”[2]

John Wright Stanly House, New Bern

Located on George Street and directly north of the Tryon Palace Auditorium stands the John Wright Stanly House, one of the first buildings saved as part of the restoration of New Bern and the first building preserved in North Carolina with a connection to Washington. The Georgian-style house was built in the early 1780s for John Wright Stanly, a wealthy New Bern citizen and patriot of the Revolution. Unfortunately, a yellow fever epidemic in the late 1780s passed through the area, taking Mr. Stanly in 1789 and his wife shortly after.[1] Six of their children survived the epidemic, but the massive house remained abandoned until the eldest son, John Stanly Jr., took possession of the property in 1798.

On April 20, 1791, Washington and his procession arrived in New Bern and for two nights lodged at the Stanly house. According to New Bern legend, the locals realized the fine house was vacant and, hearing of Washington’s planned visit, chose to repair and open the house, putting “their own furnishings inside for Washington.”[2] Washington’s diary provides few details about his time at the Stanly House, only describing the place as “exceeding good lodgings.”[3] In 1798, John Stanly Jr. moved into the house and resided there until the mid-1820s. During the Civil War, New Bern was occupied by Federal forces, during which residential homes were converted into hospitals and headquarters. The Stanly house was used as both, first serving as the headquarters of General Ambrose E. Burnside before being used by the Sisters of Mercy, a group of Catholic nuns who acted as nurses for Federal hospitals.[4]

In 1935, the Stanly House was restored with labor from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a program established in 1935 under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to create jobs for unemployed workers following the Great Depression. Following the restoration, the house was used as a public library.[1] From 1935 until 1965, the house served as the New Bern Public Library under the New Bern Library Association. In 1965, the Tyron Palace Commission was gifted the John Wright Stanly House from the New Bern Library Association, and the following year, the house was moved to the Tryon Palace Complex.[2] In 1972, the house was open to the public as a historic house museum.[3] Currently, the inside of the house is closed to the public, but guests are welcome to stroll through the property’s garden. The Tryon Palace website includes a history of the house, a brief telling of its preservation, and opens with the tagline “Generations of Stanly’s … and George Washington slept here!”[4]

Salem Tavern, Old Salem

Located in the backcountry of North Carolina is the Moravian settlement of Salem, which contains the third preserved building that claims Washington slept here, the Salem Tavern. In the middle of the 18th century, a group of Germanic people known as the Moravians settled in North Carolina. Tracing their faith to the 15th-century priest Jan Hus, the Moravians are followers of one of the earliest Protestant groups officially known as the Unitas Fratrum (Unity of Brethren) and had arrived in the colony in the 18th century to escape religious turmoil within Central Europe. In 1753, the Moravians purchased the Wachovia Tract, and in 1766, the first tree was felled for the creation of Salem. The Moravians designed Salem as a self-sufficient community and built their town to be an industrial center not just in Wachovia but within North Carolina’s “back country.”[1]

The settlement’s industry within the backcountry of the colony led to the first tavern in Salem to be constructed in 1771. Unfortunately, the first tavern did not last long, as it burned down in 1784. Known as skilled craftsmen, residents of Salem quickly rebuilt the tavern on the remaining foundation within the year.[2] As a congregation that left Europe due to conflict, during the Revolution, Salem and the Moravian settlers chose not to get involved in the war.[3]The Moravians’ lack of involvement in the Revolution did not stop Washington from visiting the town for two nights, nor dampened the locals’ interest in his arrival.

On May 31, Washington arrived in Salem and spent two nights at the Salem Tavern. In his diary, Washington described the village as “small but neat” and noted it “having within itself all kinds of artizens [sic].”[4] The following day, June 1, Washington spent the morning “visiting the Shops of the different Trades Men … & their place of worship,” and later dined with several “principal people.”[5] The next day, Washington and his caravan set out from Salem towards Guilford, leaving behind yet another tavern that would claim “George Washington slept here.”

Salem Tavern continued to be used as a place for travelers to rest and eat, and by the late 19th century, the building was renamed the Salem Hotel. During this time, Salem was developing into the modern age, and by 1890, trolley cars were located on Main Street.[6] By the 1930s, the restoration project of Colonial Williamsburg and South Carolina’s zoning of the nation’s first historic district in Charleston sparked Salem’s preservation movement. In 1948, Winston-Salem was labeled as a historic district to save and preserve historic buildings and the character of the city. In December 1948, the city adopted a zoning ordinance for Salem and established the Old and Historic Salem District.[7]

In 1929, before the creation of the historic district, Salem Tavern was saved from demolition by Miss Ada Allen and her sister, Annie, who purchased the building to use as a home. The Allen sisters lived in the Salem Tavern until 1939, when the building was purchased by the Wachovia Historic Society.[1] Founded in 1895, the Wachovia Historical Society (WHS) is the oldest historical society in North Carolina, and shortly after their founding began purchasing historic buildings within Salem for their preservation.[2]

In 1950, Old Salem, Inc. was incorporated with the goal of purchasing historic properties within the city to preserve and open them to the public.[3] In their first year, Old Salem, Inc. had only four properties, none of which were viewed as “of primary importance at that time.”[4] The organization believed that the best way to attract the public’s interest in the preservation of Salem was to get a few of the city’s major historic buildings — the Boys School, the Salem Brothers House, and, of course, Salem Tavern. In 1953, the Wachovia Historic Society was not interested in selling the tavern and instead agreed to lease the tavern to Old Salem, Inc. for 50 years.[5] As part of the lease, Old Salem, Inc. agreed to complete the restoration of the building and open it as a house museum; in 1956, 165 years after Washington’s visit, the Salem Tavern was opened to the public.[6] Today, the Salem Tavern remains open for visitors, with tours discussing the history of trade between Salem and the backcountry of colonial North Carolina, the use of taverns during the era, and, of course, showcasing the very room Washington slept in for two nights.

Eagle Tavern, Halifax

The final building connected to Washington for this paper is located in Halifax, site of North Carolina’s first step in the Revolution and arguably its most influential contribution, the Halifax Resolves. On April 4, 1776, North Carolina’s Fourth Provincial Congress gathered in Halifax to discuss how the colony would address the issues being raised within the Continental Congress. The Provincial Congress agreed that independence from Great Britain was called for, and on April 12, 1776, a report was submitted that stated “that the delegates for this colony [North Carolina] in the Continental Congress be empowered to concur with the delegates of the other Colonies in declaring independency.”[1] This document became known as the Halifax Resolves and became the first official provincial action for the colonies’ independence.

When Washington visited Halifax, he made no mention of this historic event having happened within the town, but instead only commented on the town’s depleting population. Unlike the other properties discussed, it cannot be confirmed where Washington stayed in 1791 while in Halifax, but early tradition claimed he slept in the Eagle Tavern. Originally, the two-story tavern was built as a house in 1760, but by 1771 the building was converted into a tavern known as “Sign of the Thistle,” later changed to Eagle Tavern, and by 1824 the building was referred to as the Eagle Hotel.[2] While local tradition claims Washington slept there, historic records do show that in February 1825, the Marquis de Lafayette lodged at the tavern during his 1824–1825 farewell tour of America.[3]

In 1838, Michael Ferrall, an Irish businessman, purchased the hotel and relocated the building in 1845 to turn it into a family home.[4] Generations of Ferralls lived in the house until Nannie Gray, the great-granddaughter of Michael Ferrall, passed away in 1969. Gray left the house to the Catholic Diocese in Raleigh, which, in turn, donated the house to the State of North Carolina. In 1976, during the bicentennial of the American Revolution, the tavern was moved for a second time within the Historic Halifax State Historic Site.[5]

Before the move of the tavern in the 1970s, a photograph of the tavern at its second location shows a historic plaque located outside the house along the road. The plaque’s date of construction is not visible, but it was likely erected in the 1930s, around the time the North Carolina State Historical Commission had road markers placed. The sign reads “Eagle Tavern: Early political & social center. Built before 1772. 4 blocks N. Washington (1791) & Lafayette (1825) were guests. Building moved here about 1845.”[1] The 1930s marker called out the local tradition of Washington having slept here, but by the 1970s, the story of Washington having slept here had faded out with no supporting historic evidence. In 1973, a National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form was submitted for Eagle Tavern that tells of Lafayette’s visit in 1825 but makes no mention of Washington or the local tradition of his staying there.[2]

Following the second move of the tavern in 1976, a new marker was placed outside the tavern in 1977, which reads “Eagle Tavern: Built in 1790s. Banquet for Lafayette held on February 27, 1825 when tavern was on the original site 900 ft. northeast,”[3] showing the claim that Washington slept there had been removed to tell an accurate account of the building’s history. Today, the Eagle Tavern is still part of Historic Halifax and is open for tours. While the building is historical and not connected to Washington, local tradition continues to say he may have been there, and for some people, that small likelihood is enough.

A tourist of North Carolina’s past

The first chapter of Old Salem: An Adventure in Historic Preservation opens with a column in a Winston-Salem newspaper that suggested “[r]estoring Old Salem was a waste of time and money.” The columnist said the trustees of Old Salem, Inc. should instead put the money towards a stage production of the play George Washington Slept Here, since Washington had slept in the Salem Tavern and was, in the columnist’s opinion, “Old Salem’s only claim to historic fame.”[1]

The point of this paper is not to say that all these places are important because of Washington, nor to say that his even visiting these places is what makes them great or historic spots. Instead, North Carolina’s connections to Washington do not center on him fighting a heroic battle at these sites or writing a great speech to call for national change. Washington’s tour reflects the journey of a man who, after a war for independence, traveled to see the country and people who made it all possible. Washington visited Halifax, where the first official call for independence was penned, three months before the Declaration of Independence. He dined and danced in the former governor’s palace in New Bern, where North Carolina’s first permanent capital was located, and where the royal governor fled before the Revolution, and he toured the village of Salem, whose citizens refused to get involved in the Revolution, and instead focused on craftsmanship and trade.

One could say that Washington was as much of a tourist visiting Tryon Palace as those today, witnessing a city once at the center of North Carolina’s colonial era, or that Washington’s stop at the battlegrounds of Guilford Courthouse are as much of a visit of reflection to the battle he and people visiting today knew of but were not part of. While Washington visited these places, it was not because of him that they were preserved. These buildings were preserved because they reflect the history of North Carolina, the story of these towns and buildings tied to the character and achievements of North Carolinians. While the preservation movement used Washington-connected places in helping to encourage connections to larger figures, the places Washington visited in North Carolina do not tell the story of him. Instead, they tell the history of North Carolina’s fight for independence and its citizens’ place in our country’s founding. For visitors of these sites, they recount the history of North Carolina’s colonial past, but for natives of North Carolina, these buildings were preserved first and foremost to remember a larger story of Carolinians who aided in the writing, fighting, and forming of a new united nation.

[1] Griffin, Old Salem, 2.

[1] “Eagle Tavern,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomation Form, 7, accessed April 2025, https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/nr/HX0002.pdf.

[2] Ibid., 3.

[3] “Eagle Tavern (E-68),” NCDR.

[1] “Halifax and the Revolution,” North Carolina: Historic Sites,” accessed June 7, 2025, https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/historic-halifax/history/halifax-historic-district-importance/halifax-and-revolution.

[2] “Eagle Tavern (E-68),” North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, updated December 13, 2023, https://www.dncr.nc.gov/blog/2023/12/13/eagle-tavern-e-68.

[3] NRHP, “Salem Tavern,” 3.

[4] Ibid., 3.

[5] “Eagle Tavern (E-68),” NCDR.

[1] “Old Salem Historic District,” National Historic Landmark Nomination, 154.

[2] “About,” Wachovia Historical Society, accessed May 2025, https://wachoviahistoricalsociety.org/about/.

[3] “Old Salem: A. Organization & Information,” City of Winston-Salem, 8, accessed June 2025, https://www.cityofws.org/DocumentCenter/View/27670/Old-Salem.

[4] Griffin, Old Salem, 40.

[5] “Salem Tavern,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form, 7, accessed April 2025, https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/nr/FY0013.pdf.

[6] Griffin, Old Salem, 41.

[1] Frances Griffin, Old Salem: An Adventure in Historic Preservation, Old Salem, Incorporated, 1970, 2-3.

[2] “Local Historic Landmark Program,” Forsyth County Historic Resources Commission, accessed April 2025, https://www.cityofws.org/DocumentCenter/View/3834/048—Salem-Tavern-PDF?bidId=.

[3] Griffin, Old Salem, 2.

[4] Founders Online, May [1791].

[5] Founders Online, [June 1791].

[6] “Old Salem Historic District,” National Historic Landmark Nomination, accessed April 2025, https://files.nc.gov/historic-preservation/nr/FY0009.pdf, 154.

[7] “Old Salem Historic District (J-126),” North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, published January 10, 2024, https://www.dncr.nc.gov/blog/2024/01/10/old-salem-historic-district-j-126.

[1] Brook, A Lasting Gift of Heritage, 6.

[2] Jerry L. Cross, The John Wright House, (North Carolina Division of Archives and History, 1987), i. Digital copy from North Carolina Digitial Collections, https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/john-wright-stanly-house/791749?item=816058.

[3] “John Wright Stanly House (C-1),” North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, modified December 6, 2023, https://www.dncr.nc.gov/blog/2023/12/06/john-wright-stanly-house-c-1.

[4] Tyron Palace, “Stanly House.”

[1] Mary S. Hessel, “Stanly, John Wright,” NCpedia, written in 1994, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/stanly-john-wright.

[2] “Stanly House,” Tyron Palace, accessed May 2025, https://www.tryonpalace.org/the-palace-historic-homes/historic-homes/stanly-house.

[3] Founders Online, “[APRIL 1791].”

[4] Tyron Palace, “Stanly House.”

[1] Brook, A Lasting Gift of Heritage, 6.

[2] Palace History, “Tryon Palace.”

[1] “Palace History,” Tryon Palace, accessed May 2025, https://www.tryonpalace.org/the-palace-historic-homes/tryon-palace/palace-history.

[2] “[APRIL 1791],” Founders Online, National Archives.

[3] Palace History, “Tryon Palace.”

[1] “Guilford Courthouse; National Military Park, North Carolina,” National Park Service History, last updated April 2025, https://npshistory.com/publications/guco/index.htm.

[2] David Louis Sterrett Brook, A Lasting Gift of Heritage: A History of the North Carolina Soiety for the Preservation of Antiquities 1939 – 1974, (North Carolina Division of Archives and History, 1997), 4.

[3] Ibid., 5.

[4] Ibid., 5-6.

[5] Ibid., 6.

[1] Washington’s Headquarters State Historic Site, “Reaching Back to a Glorious Past,” Newburgh, New York.

[2] “Washington’s Headquarters State Historic Site,” New York State, accessed May 2025, https://parks.ny.gov/historic-sites/17/details.aspx.

[3] “Morristown National Historical Park,” Washington Association of New Jersey (WANJ), accessed May 2025, https://wanj.org/morristown-national-historical-park/#:~:text=The%20Ford%20Mansion%20and%20Museum&text=built%20the%20mansion%20as%20his,troops%20quartered%20at%20Jockey%20Hollow. “Natural Resource Monitoring at Morristown NHP,”National Park Service, accessed May 2025, https://www.nps.gov/im/netn/morr.htm.

[4] John H. Ansley, “Chapter Two: The Centennial and Memorial Association of Valley Forge,” in Valley Forge: Making and Remaking a National Symbol, (Pennsylvnia State University Press, 1995), https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/vafo/treese/treese2a.htm.

[5] Edward G. Lengel, Inventing George Washgington: American Founder, in Myth and Memory (HarperCollins Publishers, 2012), 106.

[6] “Community Chatter,” Nebraska Daily News-Press, October 4, 1939, 4. Accessed July 2024, https://www.newspapers.com/image/729122080/.

[7] “George Washington Slept Here Historic Markers: He slept in a lot of places,” The Historic Markers Database, accessed March 2025, https://www.hmdb.org/results.asp?Search=Series&SeriesID=9.

[1] “[April 1791],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-06-02-0002-0003. [Original source: The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 6, 1 January 1790 – 13 December 1799, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979, pp. 107–125.]

[2] Warren L. Bingham, George Washington’s 1791 Southern Tour, (History Press, 2016), 67.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Lindley S. Butler, and John Hairr, “Wilmington Campaign of 1781.” NCpedia. Encyclopedia of North Carolina, University of North Carolina Press, accessed on June 3rd, 2025, https://www.ncpedia.org/wilmington-campaign-1781.

[5] “The Liberty Trail; An Unforgettable Journey Through Place and Time,” American Battlefield Trust, accessed June 3, 2025, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/libertytrail.

[6] “May [1791],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-06-02-0002-0004. [Original source: The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 6, 1 January 1790 – 13 December 1799, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979, pp. 125–153.]

[7] “[June 1791],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-06-02-0002-0005. [Original source: The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 6, 1 January 1790 – 13 December 1799, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979, pp. 153–167.]

[8] Ibid.

[9] William Byrd, The Dividing Line Histories of William Byrd II of Westover, ed. Kevin Joel Berland (University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 65.

[1] “From George Washington to the Great Dismal Swamp,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-01-02-0009-0001. [Original source: The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 1, 11 March 1748 – 13 November 1765, ed. Donald Jackson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976, pp. 319–320.]