- President Trump recently expressed interest in promoting a 50-year mortgage

- Still, 50-year mortgages would barely improve affordability while massively increasing lifetime interest costs

- Long-term mortgages risk driving home prices higher by boosting demand without adding supply

President Donald Trump recently revived talk of a 50-year mortgage. On Truth Social, he shared an image of Franklin D. Roosevelt labeled “30-year mortgage” beside a photo of himself marked “50-year mortgage.” The post has reopened a debate long considered settled over whether ultra-long home loans are a good idea.

The renewed interest in 50-year mortgages might sound like a bold new plan to help Americans afford homes. The idea of ultra-long mortgages is not new, however. It appeared briefly before the 2008 housing crash but never gained much traction — and for good reason. Once you dig into the math, the market dynamics, and the long-term implications for borrowers, a 50-year mortgage looks far less like a solution and far more like a gimmick that papers over deeper, structural issues.

The interest rate problem

Start with the most basic problem: the rate. Mortgage rates aren’t assigned based simply on the term length; they’re value judgments made by investors holding the debt. A standard 30-year mortgage doesn’t actually behave like a 30-year asset, because most borrowers sell or refinance before they reach the end of the term. That’s why 30-year mortgage rates track the 10-year Treasury yield, not the 30-year one. Today, the average spread is around 210 basis points, and with the average 30-year mortgage at an interest rate of about 6.22 percent, the market can price that product with a fairly high degree of confidence.

A 50-year mortgage would be a very different creature. Investors would be stuck with a long-duration asset that’s unlikely to be refinanced since for most borrowers, refinancing from a 50-year into a shorter-term loan would only raise their payment, not lower it. That means the typical prepayment risk almost disappears. The benchmark for pricing such a product would shift toward longer-term bonds, such as the 20-year Treasury at 4.67 percent, or the 30-year at 4.71 percent. Even under generous assumptions, the interest rate on a 50-year mortgage would almost certainly be higher than that of a 30-year. A modest estimate puts the difference at about 30 basis points, placing a current 50-year mortgage somewhere around 6.5 percent.

Supply-side issues simply cannot and should not be fixed with demand-side solutions.

This difference matters enormously over such a long stretch of time. A borrower with a $300,000 loan at 6.2 percent on a 30-year schedule would end up paying around $380,000 in interest. Switch to a 50-year mortgage at 6.5 percent, and the interest bill rockets up to more than double: over $750,000. Even if the 50-year mortgage shared the same interest rate as the 30-year, the longer payoff schedule would still result in over $700,000 in lifetime interest. No amount of monthly payment smoothing can erase the reality that stretching a mortgage across half a century would force someone to pay dramatically more for the exact same house.

Equity will grow at a glacial pace

The costs wouldn’t be merely financial. One of the great virtues of the traditional, 30-year mortgage is that it gradually transforms debt into home equity. That equity becomes a buffer against recessions, a path toward financial stability, and, for many families, their most important asset. But equity grows painfully slowly even on a 30-year schedule. On a 50-year term, it would grow at an even more glacial pace.

To illustrate the difference: A 30-year mortgage at today’s rates on a $300,000 loan would pay down around $19,000 in principal after five years and around $45,000 after 10 years, which is about the average length of homeownership in the U.S. With a 50-year mortgage, however, after five years, the borrower would eliminate only about $4,000 of principal, barely more than 1 percent of the loan. After a decade, only about $10,000 of the original $300,000 would be paid down. It would essentially create permanent indebtedness, with borrowers functioning more like long-term tenants who happen to hold a deed.

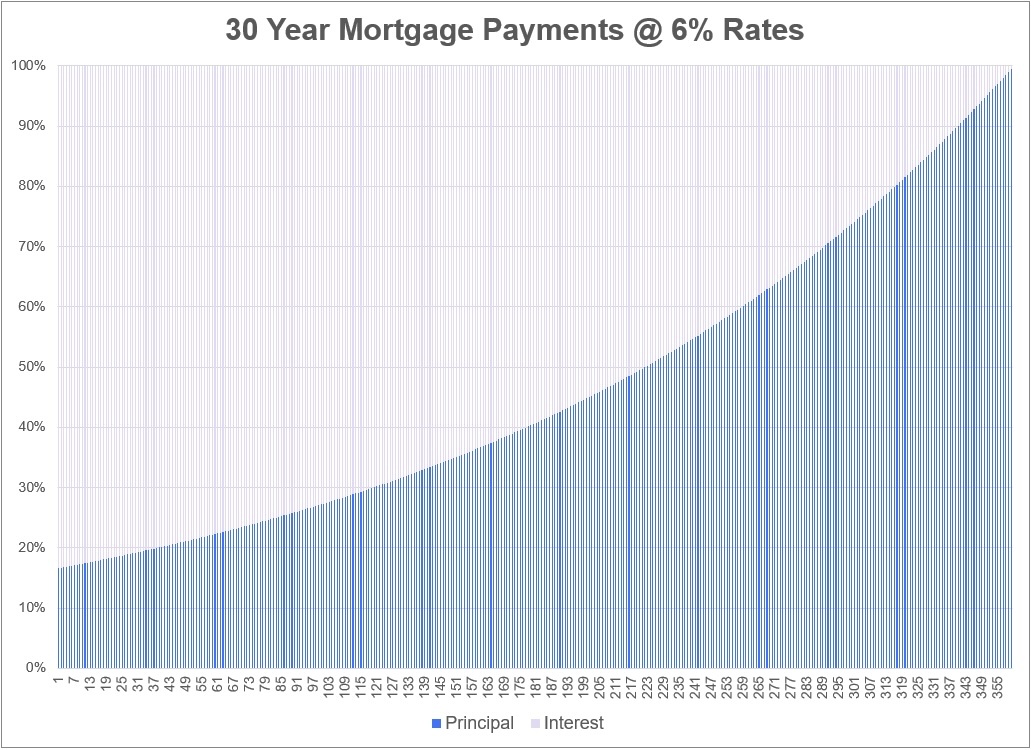

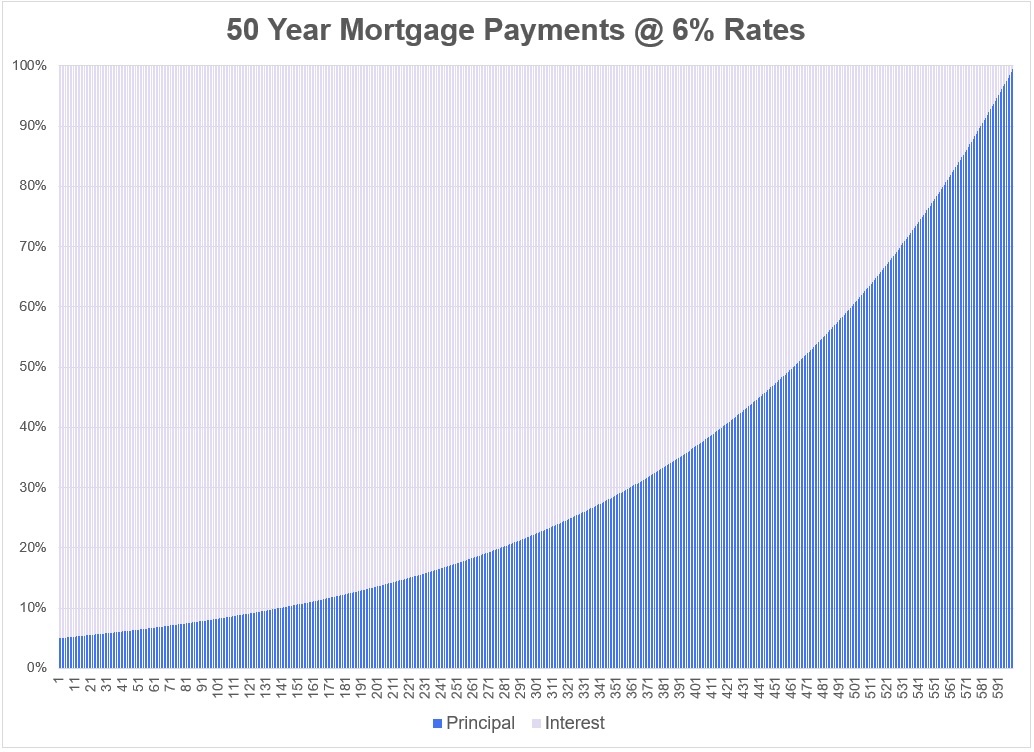

The figures below show the split between principal and interest over the course of the mortgage term. The graphics show just how different the schedules look for each loan term, and how, for a 50-year mortgage, the first several years would be spent almost entirely paying off interest. The x-axis shows number of monthly payments, while the y-axis shows the percent of principal versus interest paid each month.

Source: https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2025/11/the-economics-of-a-50-year-mortgage

This lack of equity would create practical problems. For example, it would make refinancing difficult or impossible. It would make moving riskier, because closing costs or small dips in home prices could erase the tiny sliver of equity a borrower had managed to accumulate. And it would leave homeowners in a more fragile financial position, precisely the opposite of the security that homeownership is supposed to create.

And what would borrowers get in exchange for taking on more interest and delaying equity? Surprisingly little in terms of purchasing power. Holding the interest rate constant at 6.5 percent, using the median cost of a home in North Carolina of $330,564, and assuming a 20 percent down payment, a borrower would need around $97,000 in income to qualify for a 30-year mortgage. Stretching the term to 50 years would barely move the needle, lowering the required income to about $91,000. That’s not nothing, but it’s certainly not transformative.

Even the supposed improvement in “purchasing power” would be far less meaningful than it seems at first. Yes, someone earning about $100,000 could stretch from a roughly $360,000 home to something around $400,000 at the same monthly payment if their loan ran for 50 years instead of 30. But the higher home price requires a larger down payment to avoid private mortgage insurance (PMI), and without that larger down payment, PMI reduces the amount of the mortgage they can qualify for. In other words, the math that seems to work on paper becomes more complicated once real-world constraints are taken into account.

The problem is supply, not demand

The greater danger is not what 50-year mortgages would do for individual borrowers but what they could do to the entire housing market. After years of frenzied price growth and record-low inventory, the market has finally entered a period of relative stability. Inventory has climbed back to around 4.6 month’s worth of supply, the highest level in a decade, and price growth has cooled to roughly 2.1 percent year over year. These are signs that the market is healing itself after pandemic-related distortions.

Injecting a new “affordability product” that would increase demand without adding supply risks undoing that newfound stability. Even a moderate rise in demand would begin to drain inventory again. Prices would start to rise faster. And whatever small affordability gains a 50-year mortgage could temporarily produce would be wiped out by higher home prices. Housing affordability can’t be fixed by gimmicks that allow people to bid more for the same scarce homes. Supply-side issues simply cannot and should not be fixed with demand-side solutions.

The fundamental barriers remain regulatory. Zoning restrictions, permitting delays, regulations and tariffs on input costs like lumber and aluminum, as well as rules that prevent denser or more diverse housing options all keep prices elevated. Builders, even when offering discounts, incentives, and temporary rate buydowns, still struggle to meet the demand for reasonably priced homes in locations where buyers actually want to live. Longer mortgage terms would do nothing to correct these structural problems. They would merely stretch homeowners’ budgets further while leaving the roots of the affordability crisis untouched.

Conclusion

Stability, less regulation, and more freedom to build is what the market needs to continue normalizing. A steady combination of gradually declining mortgage rates, modest income growth, slower home price appreciation, and increased construction is the only sustainable path forward. A 50-year mortgage, by contrast, would multiply costs, trap borrowers in debt, erode wealth-building, push prices upward, and offer only marginal, fragile affordability gains in return. It is not a new idea, but it is still a terrible one.

If policymakers want a housing system that is affordable, stable, and sustainable, the answer is not to stretch mortgage debt across half a century but to tackle the supply crisis head-on — because no mortgage structure, no matter how creative, can compensate for the simple reality that the country has not built enough homes where people want to live.