Introduction

The United States Constitution does not mention education. From our nation’s infancy, Congress generally adhered to the principle that the federal government had no authority to undertake functions and duties not enumerated in the Constitution. As such, the nation relied on families, communities, and state and local governments to direct the education of the citizenry. As an acknowledgment of this fact, all fifty states, including North Carolina, include passages on public education in their state constitutions and statutes.

This was the reigning orthodoxy until the mid-1960s. The passage of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) in 1965 changed all that.

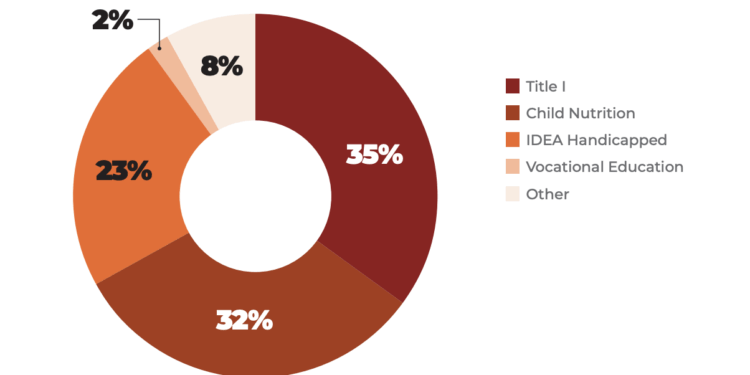

Since the rise of federal activism after World War II, Congress has continued to enlarge the federal government’s financial and regulatory role in public education. By the middle of the 1960s the federal government had committed to aiding local state departments of education, low-income students (Title I), and special-needs children (Title VII), all via the ESEA Act of 1965 and amendments in 1966. Growing federal programs such as child nutrition (National School Lunch Program) and vocational education (Perkins Act) continued to expand the federal role in education.

At no time before, however, did the federal government’s role become larger or more controversial than Congress’ 2002 reauthorization of the 1965 ESEA, also known as No Child Left Behind. This bipartisan law imposed new testing, reporting, and accountability requirements on states, which they begrudgingly implemented to keep federal K-12 education dollars flowing into state coffers.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) was the latest reauthorization of the ESEA and borrows from the No Child Left Behind blueprint. Pres. Barack Obama signed ESSA into law in December 2015. Subsequent presidential administrations have been responsible for its implementation.

It didn’t take long for the requirements to start accumulating. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Education required state education agencies to submit a consolidated state plan detailing how their public education systems will comply with the law’s various requirements. State education officials were also required to identify and initiate research-based interventions in the state’s lowest-performing schools. Like No Child Left Behind, ESSA also required states to administer math and reading tests to students in grades 3-8 and high school. States must report those results in the aggregate and by student racial and demographic subgroups. Another provision required all states to begin reporting school-level financial data to the department starting in 2019.

More recently, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, three pieces of federal legislation distributed about $190 billion to K-12 schools nationally. About $6.2 billion of those funds were allocated to North Carolina around $4,000 per public school student. The federal aid required massive development of plans and reporting requirements for states and local school districts as a condition of receipt of funds.

In an average year, federal support for K-12 education in North Carolina would be about 10% of all funds. Most of those funds would be spent on Title I schools for poor or disadvantaged children, aid for special-needs children, and child nutrition programs.

The federal response to Covid changed all that. As a percentage of total support, federal dollars now comprise about 20% of all funds; state support, about 60%. Local funds make up the remaining 20%.

The increase in the federal role has given the federal government a greater presence in an area where they have traditionally not been a major player. The increase in federal programs means more applications, more program monitoring, more program reporting, and more administrative costs. Furthermore, the costs of compliance are more than monetary. The increase in administrative overhead erodes school level leadership based on the needs of students.

Accountability is important, but we also need to ask, accountability to whom and for what? Funding needs to be targeted on the right ends. North Carolina’s $6.2 billion in federal Covid relief dollars came with significant administrative and reporting requirements but no apparent overall strategy. The federal government provided little oversight over how schools choose to spend Covid funds and, even worse, no requirement to demonstrate those funds are accomplishing their intended purpose.

It’s characteristic of federal intervention as a whole: distracting because of the many compliance burdens it puts on states and localities. They give the federal government a sizeable presence in state accountability efforts. The federal government’s growing financial and ideological encroachment into public education is worrisome. It invites the kind of centralization of public schooling wisely resisted by most Americans and detracts from true, proper accountability to those who have the most at stake in education: parents, students, and other taxpayers.

Key Facts

- While most federal education funds are earmarked for special-needs children, low-income students, child nutrition, and vocational education, Congress will occasionally authorize discretionary, multiyear initiatives. They have included the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (also called the “Stimulus”) during the Great Recession and the multiple Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) grants awarded during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Expenditures from federal funds state aid and grants – totaled $3.3 billion and accounted for 20% of North Carolina’s $16.7 billion public school operating budget for the 2021-22 school year. It contributed about $2,460 in funding per student – slightly more than local per-student funding ($2,458) and considerably less than state-provided funding per student ($7,426).

- Federal Covid relief funding will inflate the federal share of public schools’ budgets and increase total public-school expenditures for at least until the end of 2024 – and in some cases even later.

- During the 2022-23 school year, North Carolina public schools used federal funds to support 15,236 public school personnel. That’s up from 12,792 public school employees, or 6.9% of all district school personnel in the state in 2021.

- Major Covid relief funding packages for K-12 schools included: $60 million from the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Fund; $387.7 million from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER I) portion of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act; $1.55 billion from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA/ESSER II); and $3.2 billion from American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA/ESSER III).

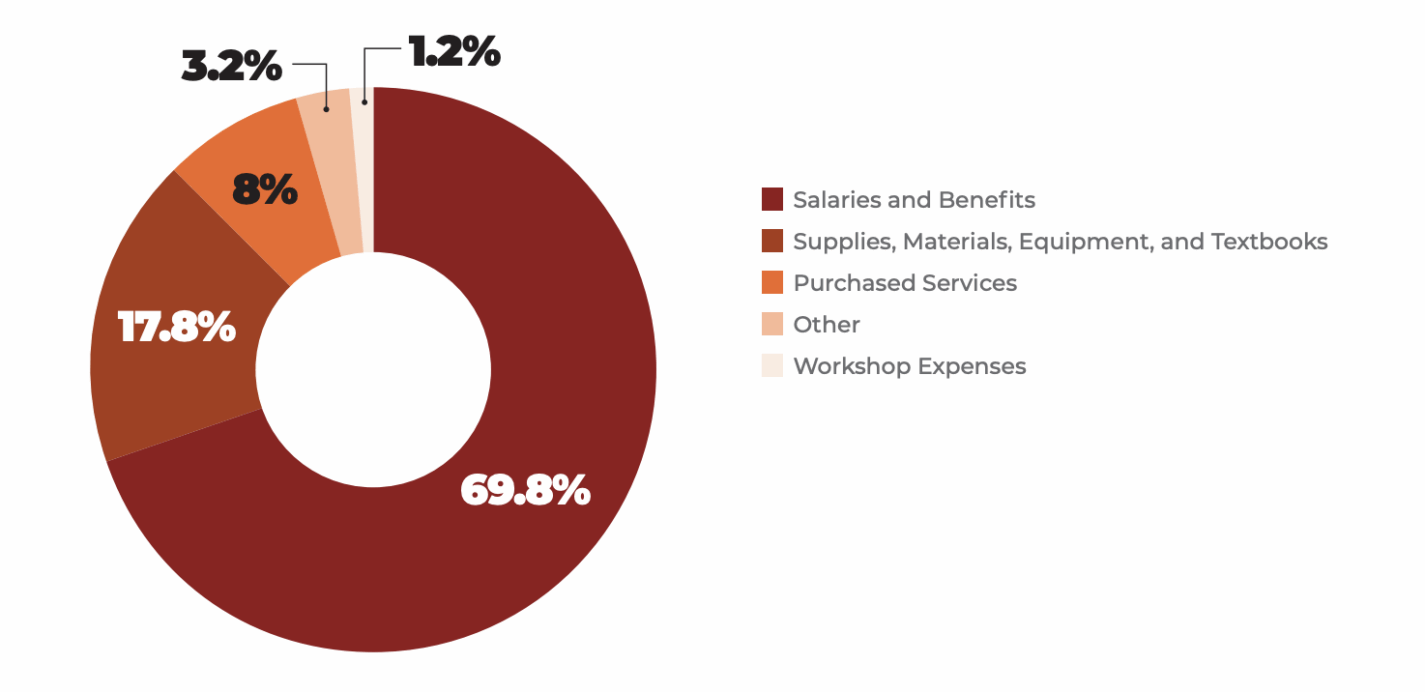

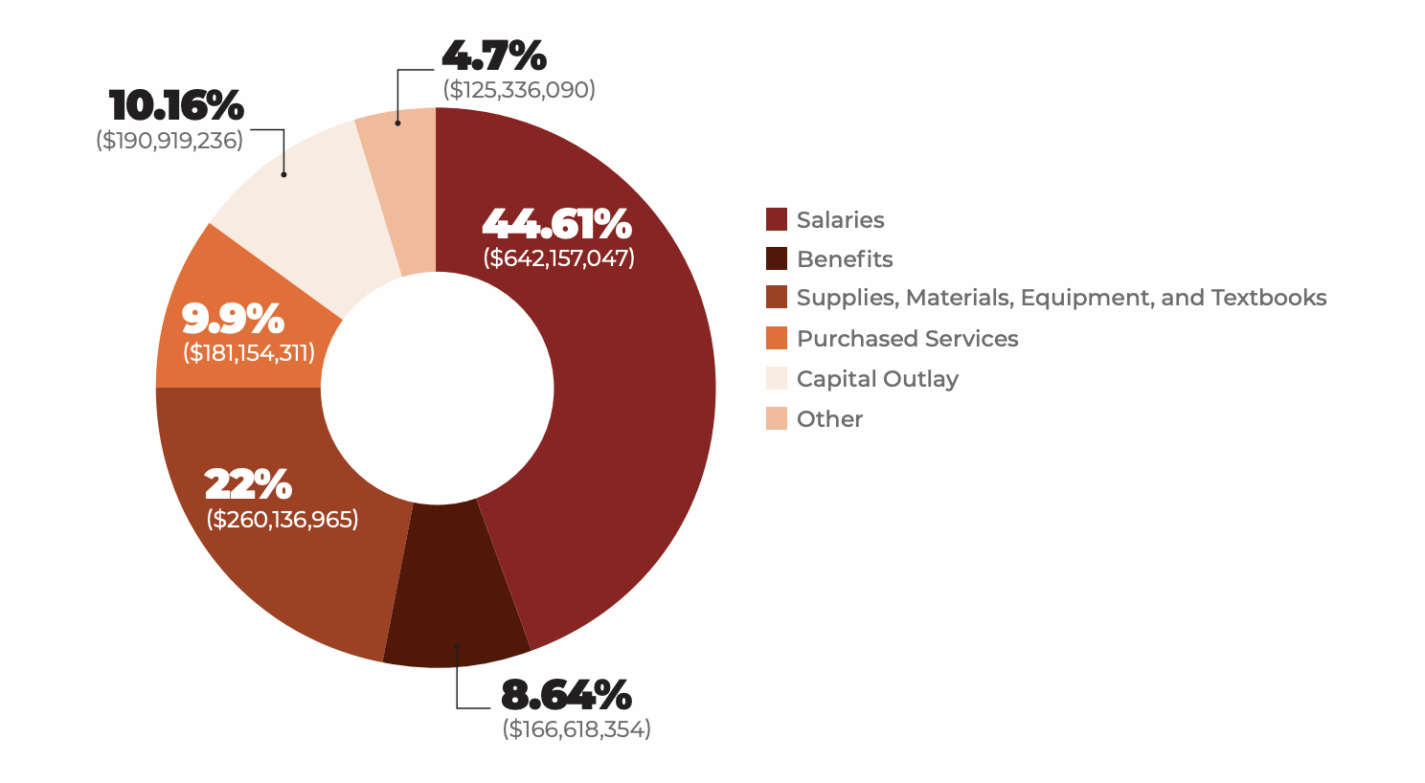

- How did North Carolina public schools spend these funds? As of September 2023, 45% of funds were spent on salaries; 9%, on employee benefits; 22%, on supplies and materials; 10%, on purchased services and capital outlay; and 5%, on other expenses.

Recommendations

1. Recognize There Is No Such Thing as “Free Money” From the Federal Government Ever.

No state has ever received federal education funding without strings attached. Meeting those requirements may place extraordinary financial and administrative burdens on its recipients. Federal training and reporting mandates for school-based administrators and educators consume time that could otherwise be spent in more productive enterprises, such as the improvement of classroom instruction.

2. Acknowledge That Federal Funds Do Not Appear Out of Thin Air.

Current and future taxpayers, not elected officials and bureaucrats in Washington, D.C., bear the burden of repaying every dollar spent or borrowed by the federal government.

3. If Using Federal Funds, Use Them Prudently.

School districts should reject invitations to use temporary federal grant dollars to fund permanent support, instructional, or administrative positions.

4. Require All Federal Grants Be Required to Include a Summary of the Costs of Compliance.

It should include listing the true costs of complying with grant regulations as well as other personnel and staff costs involved. Policymakers should be provided this assessment to know the full administrative, financial, and economic costs of taking federal dollars.

5. Restructure Federal Grants.

Federal grants should be structured so that not only can dollars be tracked, but also their impact. States should be able to show what impact grants have had. Have they accomplished their intended purpose? Currently all we can show now is how much in federal funding has been spent.

Federal Funds Received FY 2022-23, includes Charter Schools but does not include Covid Funds

Source: Highlights of the North Carolina Public School budget, 2023

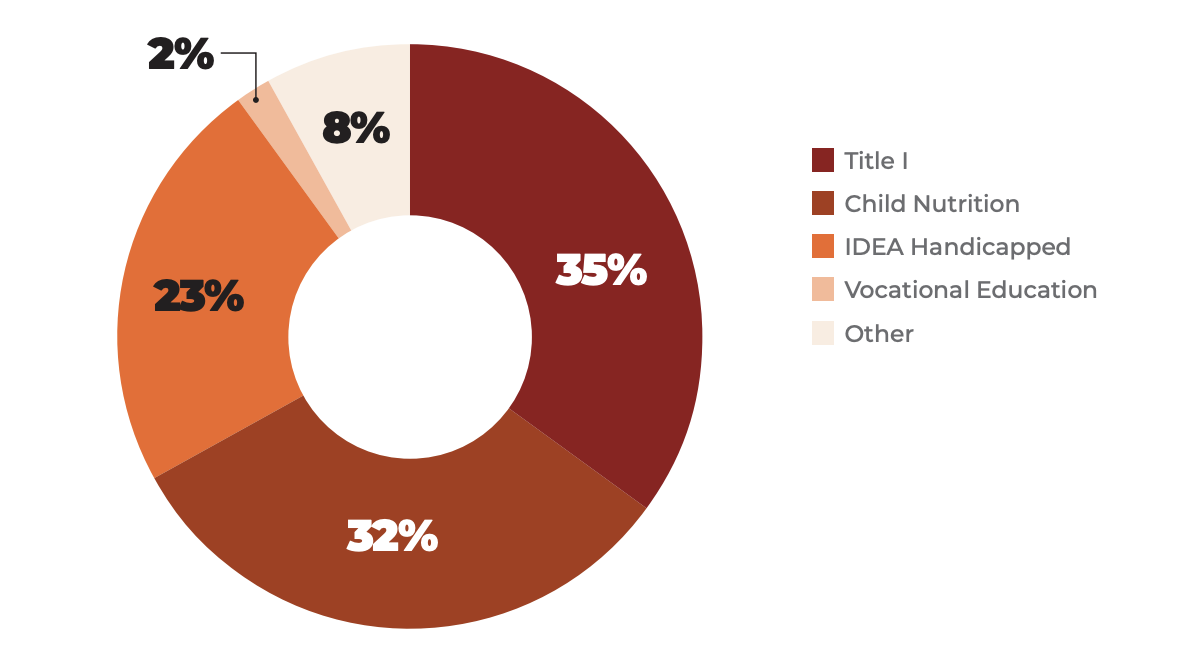

Federal Funds Expenditures 2021-22, does not include funding in response to Covid

Source: Highlights of the North Carolina Public School budget, 2023

Total Covid Expenditures FY 2023

Source: Covid funds: expenditure and allotments data, North Carolina Department of Public Instruction