Introduction

Article IX, Section II of the North Carolina State Constitution speaks to the state’s responsibility for public education when it declares, “The General Assembly shall provide by taxation and otherwise for a general and uniform system of free public schools” and “wherein equal opportunities shall be provided for all students.”

By law, North Carolina is charged with funding general school operations known as current expense. North Carolina General Statutes § 115C-408 stipulates the state will fund operational instructional expenses from state revenue. The same statute makes North Carolina counties responsible for building, equipping, and maintaining school facilities. It also states counties can supplement state school operating expenses.

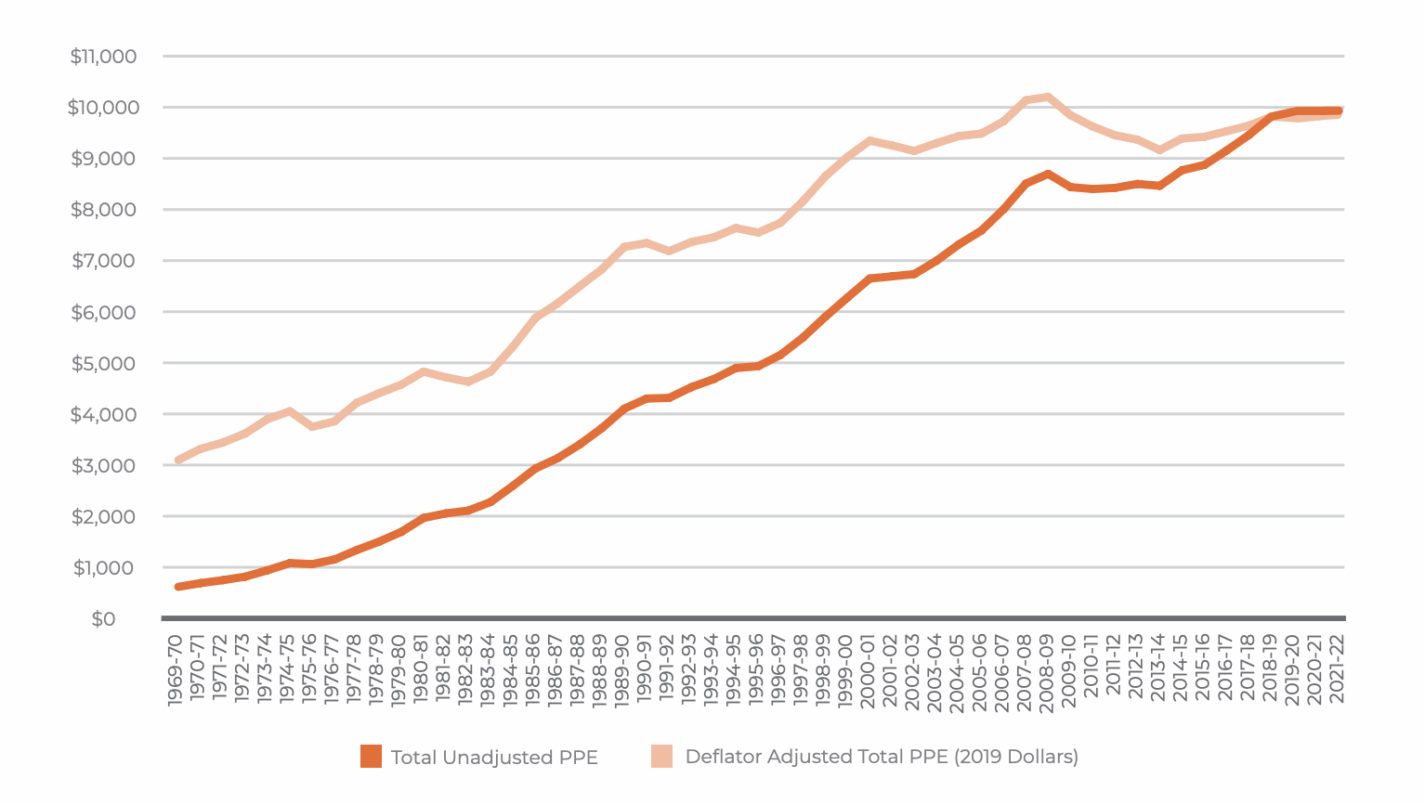

In 2021-22 North Carolina spent $16.7 billion on K-12 public education. Of that amount, $10 billion came from state government and approximately $3.3 billion each came from local and federal governments. In 2021-22, North Carolina state government provided local public schools 60% of all revenue. Local and federal government accounted for about 20% each of the remainder. In addition to current expenses, state government also distributes supplemental funds to educate specific populations such as special-needs students, at-risk students, and gifted and talented students. In addition, the state also provides special financial support to small or low-wealth districts.

How the state best finances these responsibilities while addressing concerns about effectiveness, equity, fairness, and efficiency is a never-ending question.

The quality of a school finance system is best judged by how well it meets the goals it’s designed to serve. Unfortunately, today most people equate the quality of a school finance system with the level of inputs associated with it – teacher pay, per-pupil funding, class size, etc. Such thinking exposes a flawed assumption that drives much public discussion on school finance: that more resources automatically mean better education and better educational outcomes.

A review of school district spending and educational outcomes reveals the linkage between spending and educational outcomes to be weak. All things being equal, why do some districts have below-average per-pupil expenditures and above-average test scores, while other districts spend considerably above the average per-pupil expenditure yet produce disappointing test scores? The truth is, improving educational outcomes is a complex issue with many variables. Clearly how money is spent is as important as how much is spent.

The complexity of answering the educational outcomes question should cause us to rethink how state government should approach public school finance. Using the term “educational productivity” is one way to improve the discussion. Educational productivity describes the important ratio of funding to student performance in order to measure the return on investment, while also considering such differences as cost of living, household income, and English language proficiency.

Because educational productivity properly reflects both sides of the education finance equation – inputs and outputs – policymakers should consider using educational productivity as a better way to assess how schools in North Carolina are financed.

Key Facts

- In 2021-22, North Carolina spent an average of $12,345 per K-12 student in federal, state, and local operating funds and $1,029 (fiveyear average) in per-student capital funds. When average spending for buildings and other capital costs is included, total per-student expenditures on public education in 2021-22 was $13,374.

- During the 2021-22 school year, state, federal, and local operating expenditures exceeded $16.7 billion.

- North Carolina distributes funds to local districts using over 40 different formulas or allotments. The allotments function as taxpayer-funded gift cards, most of which come with restrictions on how the money can be used. The allotments are essentially state grants and range from funding teachers and instructional staff to providing funding for driver education programs.

Recommendations

1. End How North Carolina Currently Funds Education via Complicated Funding Formulas.

Policymakers on both sides of the aisle know the current method of funding schools in North Carolina is too complicated and centralized. It offers little flexibility and transparency and makes it difficult to determine if funding is being used effectively and efficiently. In place of the current system, funding should be linked to the students. Doing so would ensure money gets to where it’s needed and also encourage accountability by not rewarding failing systems.

2. Create an Education Productivity Index Using a Dashboard of Inputs and Outcomes for Each School District and Charter School.

Educational productivity is a better indicator of the quality of a school finance system than how schools are currently evaluated. A dashboard of relevant financial, institutional, academic, and economic indicators can help to inform the public of school and student performance and encourage school districts to be more transparent.

3. Publicize Research on Education Spending and Outcomes.

Policymakers and the public need to be educated about the weakness of the link between spending and educational outcomes. Good decision-making understands both sides of that equation.

4. Require School Districts and Charter Schools to Post Budgets, Contracts, Check Registers, and Other Financial Documents Online.

Parents and policymakers lack information about school and school district spending. As such, it’s difficult to know if schools are making wise decisions about spending. Requiring schools to post spending records would improve financial transparency and aid decision-making.

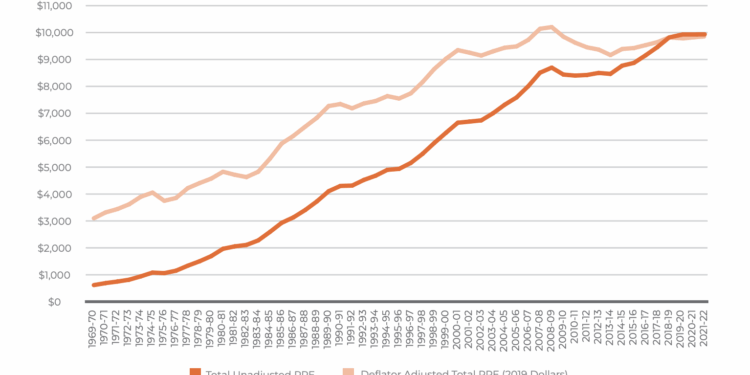

Inflation-Adjusted and Unadjusted Per-Pupil Expenditures, 1970-2022

Source: N.C. Department of Public Instruction (author’s calculations)

Total Unadjusted Expenditures

Source: N.C. Department of Public Instruction