Governor Hochul is hingeing a big chunk of her budget – and the state’s health-care system – on a politically fraught gambit: asking the Trump administration to help cover immigrants.

Hochul is seeking federal permission to temporarily continue Essential Plan coverage for 525,000 legally present non-citizens, even though they lost eligibility as part of last summer’s One Big Beautiful Bill, also known as H.R. 1.

If the feds say no, the budget Hochul proposed on Tuesday calls for shutting the Essential Plan down completely in July, which would leave most of its 1.8 million enrollees scrambling for alternate coverage.

State officials have not explicitly raised the shut-down possibility before, and enrollment in the Essential Plan has continued. Yet the governor’s newly released financial plan assumes the EP will end after June 30, and lowers its numbers accordingly.

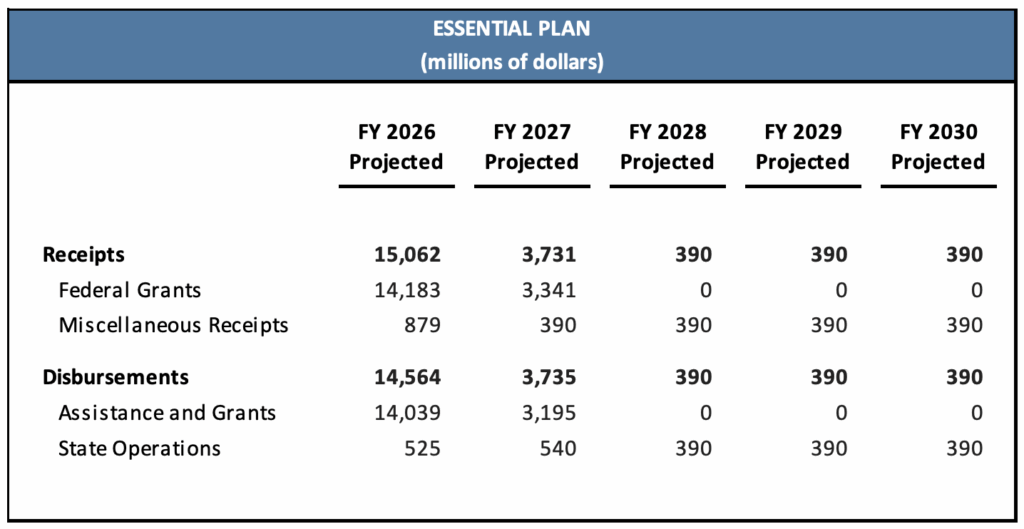

This is why her budget shows federal funding to the state plunging by $10.4 billion, or 11 percent, in fiscal 2027. It also means the overall state spending total of $260 billion – which includes federal aid – would increase by just 0.7 percent, even as the state-funded portion of the budget would surge by 5.7 percent.

Whether Hochul is fully prepared to follow-through on her shut-down ultimatum – and whether it makes fiscal sense – is unclear.

Source: NYS Budget Division

Her budget briefing book says the state “cannot afford” to operate the Essential Plan under its current design, but provides no revenue or spending estimates to support that argument.

Nor does it show the math behind the overhaul it requested last September, which would scale back the ceiling on income eligibility – to from 250 percent to 200 percent of the poverty level – displacing some 450,000 current enrollees.

Instead, the state’s financial plan shows funding for the EP dropping to a quarter of its current level, or $3.2 billion, which would cover April through June, and zeroing it out for future years.

Confusingly, the governor’s formal budget legislation allocates $6.4 billion for the program – which appears to be roughly what it would cost to run if federal officials approve the state’s requested changes.

Ironically, it’s citizens, not immigrants, who have the most to lose.

Under a 2001 ruling by the state’s highest court, in Aliessa v. Novello, New York is constitutionally obliged to cover most of the EP’s immigrant enrollees, who have incomes below 138 percent of the poverty level, regardless of whether federal aid is available or not. If the EP shuts down, this Aliessa cohort would shift to Medicaid at full state expense, which officials have estimated would cost $3 billion per year.

Under the state’s request to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the state would be allowed to pay this expense by drawing upon a $9 billion-plus surplus EP’s trust fund, which would be enough to last two to three years.

For the EP’s citizen enrollees, who have incomes above 138 percent of poverty, the alternative is private coverage, either through an employer or the Affordable Care Act. Those buying ACA plans would have to contribute at least a portion of the premium on a sliding scale – up to about $272 per month – a jarring change compared to the EP, which is premium-free.

The complexities of this policy change grow out of the topsy-turvy finances of the Essential Plan, which was launched in 2015 under a little-used provision of the ACA. States were given the option of creating a “basic health program” for people up to 200 percent of the poverty level – and receiving federal aid equal to 95 percent of the value of premium tax credits the enrollees otherwise would have received.

This option was especially valuable to New York, because it allowed the state to move Aliessa immigrants from state-funded coverage in Medicaid to federal funded coverage through the Essential Plan.

The funding formula proved to be unexpectedly generous to New York’s plan, covering all of the the program’s costs and then some, causing billions in surpluses to build up in a trust fund. This continued even as enrollment surged to almost 1.8 million – and after the state increased reimbursement rates to providers and, in 2024, expanded eligibility to 250 percent of the poverty level.

One factor behind the surpluses was the Aliessa population, who, because of their low incomes, qualified for the maximum possible subsidies. It appears, in fact, that the plan’s immigrant enrollees were cross-subsidizing its citizen enrollees.

That arrangement came to an end last summer, when President Trump signed his tax- and budget-cutting package into law. Among other cost-cutting moves, H.R. 1 barred legally present immigrants, including the Aliessa group, from eligibility for the ACA and other federal health programs.

State officials have estimated that this change, which took effect Jan. 1, will cost the Essential Plan $7.6 billion annually, or more than half of its revenue.

To continue the existing program under the changed rules, the state would likely have to cut expenses, contribute its own money or both. Officials have not said exactly how much of either would be necessary, but the gap could easily mount into the billions.

Rhetorically, the governor can try to blame Washington for any bad outcomes. But she boasted in her budget presentation that the state’s tax revenues and cash reserves have surged to all-time highs under her watch. If the state is not willing to fill budget holes in the Essential Plan, it’s not clear why the federal government, which is running trillion-dollar deficits, should do so instead.

There’s a case to be made for scaling back or eliminating the Essential Plan. It has diverted hundreds of thousands of potential customers from the state’s commercial insurance market, weakening the risk pool and driving up premiums for those who don’t qualify for subsidies.

Still, its hundreds of thousands enrollees signed up in good faith. If Hochul truly intends to take away that coverage barely five months from now, she owes them fair warning – and a much clearer explanation of why her decision is necessary.