At the July 24th Sound Transit Board meeting agency staff gave a presentation outlining an “Enterprise Initiative” intended to “…ensure we can deliver the greatest benefits of ST3 within available financial capacity”. The presentation informs us the outcome of the effort is adoption of “…an updated System Plan, with modified capital and operating plans”.

You might not guess from the “Enterprise Initiative” title that this effort has been made necessary by cost increases so big the plan can’t be implemented within expected revenues. The PowerPoint presentation is devoid of cost data so we don’t know how large the budget gap has become, but it is now too big to paper-over. As a result, the Sound Transit Board will have to make difficult decisions about what projects and services in the plan will be deferred to an uncertain future date or cancelled altogether.

The Sound Transit Board probably sees this as an unfortunate turn of events, but if they give the situation careful consideration they will realize it is actually an opportunity to replace unaffordable and ineffective elements of the ST3 plan with projects that provide greater mobility benefits to more of the region without busting the budget. Citizens have been asking for consideration of those alternatives since before the ST3 plan was adopted, but Sound Transit’s planning process has been impervious to all such suggestions.

Sound Transit has run into serious problems in the past, which the Board has viewed in terms of revenue shortfalls even when revenue wasn’t really the problem. For instance, in 2001 Sound Transit revealed the cost of the original plan was more than a billion dollars over what voters had been told. In 2009 updated financial information necessitated postponing ST2 projects that had been approved only a few months earlier, and again in 2020/2021, when the Sound Transit Board went through a seventeen-month process to “re-align” the ST3 plan to make it affordable.

Well, seemingly affordable until now.

This focus on revenue is all the more remarkable considering Sound Transit hauls in more than $2.5 billion per year from sales tax, property tax, motor vehicle excise tax, farebox revenue, interest on their billions of dollars in reserves, and Federal grants. The average household in the region pays over $1,700 per year in taxes to Sound Transit, a figure the financial plan assumes will increase in the years ahead (ever wonder why the cost of living is so high in the Puget Sound region?). That generous level of public funding, among the highest of transit agencies in the U.S., should prompt the Board to ask whether the fundamental problem might be the agency’s fixation on expensive light rail projects rather than below forecast revenue.

It is unclear whether the “enterprise initiative” will re-examine the basic assumptions that have been unquestioned since adoption of the Sound Move Plan in 1996, but as the agency’s recurring problems suggest, an objective review of the decisions that have led to the current situation is long overdue. If the “enterprise initiative” turns into just another exercise in applying financial band aids, it won’t lead to the needed reforms or produce the desired outcome.

When faced with problems in the past the Board usually assumed Sound Transit could grow its way out of near-term financial difficulties. Given time, revenues have rebounded, but the problems persist and have now grown to the point where there is no easy fix.

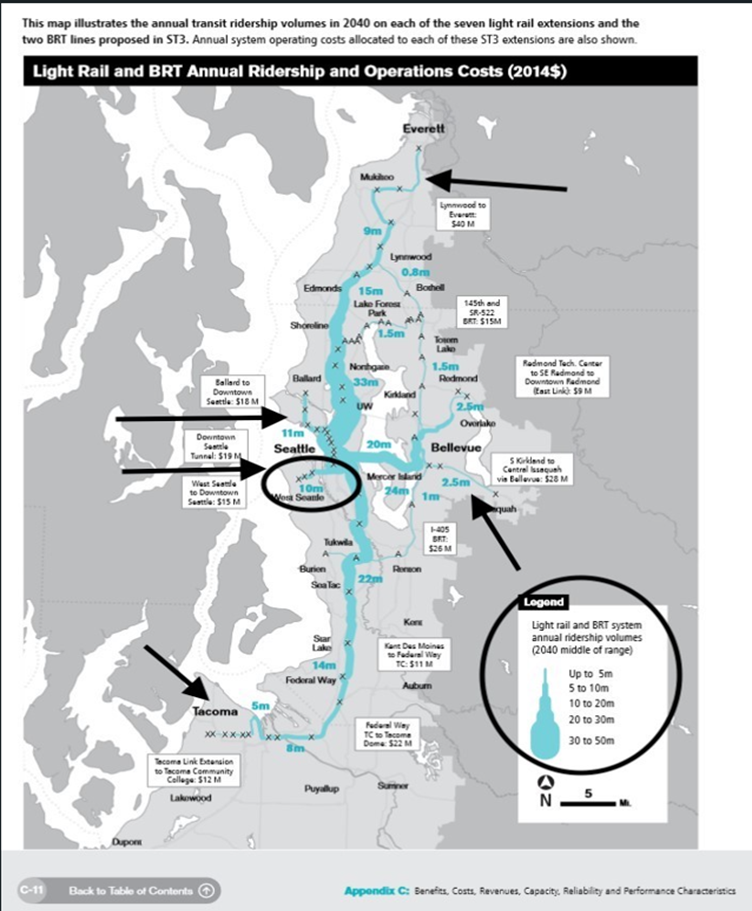

The graphic below shows why expansion of the light rail system won’t solve Sound Transit’s financial or ridership problems. The map was prepared by Sound Transit for the 2016 ST3 ballot measure. Line width indicates the ridership forecast for each segment of the system.

Far and away the most productive parts of the system have already been built or are scheduled to open soon. The high-cost extensions planned for ST3 are expected to carry far fewer riders, and as we’ve seen post-COVID, ridership is below the optimistic forecasts used to develop the ST3 plan. Even the highest ridership parts of the system are falling short of the ridership forecasts in the Puget Sound Regional Council’s 2050 Plan. That plan called for Sound Transit to carry about 3% of trips in the region, which in the greater scheme of things doesn’t represent much of an increase in mobility. To make matters worse the post-COVID reality is actual transit ridership is barely half the level called for in the PSRC plan. That by itself would be reason to reconsider the current system plan, but the failure of the region’s enormous transit investment to increase transit mode share has not been acknowledged by Sound Transit or PSRC. Rather than growing their way out of problems, building the light rail extensions will greatly increase costs while adding very few new riders. This will exacerbate the budget problem and it won’t reverse the region’s unfavorable performance trends.

The bottom line is that Sound Transit has pursued an inflexible system plan with many high-risk elements based on optimistic or outright erroneous assumptions. Now the agency finds itself in a pickle. They can either try again to band aid over their financial problems, or take a step back and ask whether expensive light rail lines that take decades to build are really a cost-effective way to meet the region’s evolving mobility needs. From a planning or engineering perspective the question is easily answered. The tricky part will be the politics of shifting to a plan that is affordable and sustainable. Sound Transit can still “deliver the greatest benefits of the ST3 Plan within available financial capacity” but to do so will requiring revisiting basic assumptions and abandoning plans for light rail projects that no longer make sense. Sound Transit’s unworkable plan has become the problem the Board needs to solve.

Sound Transit’s predicament might also prompt the Board to wonder how the agency got into such an awkward spot. After all, the Puget Sound region has experienced strong population and economic growth, and Sound Transit’s plans have supposedly been carefully developed with oversight by Board committees, a Citizens Oversight Panel, Expert Review Panels, State Auditors and Federal agencies. But the years of delay, cost increases, and low ridership all indicate that Sound Transit’s byzantine process hasn’t produced the effective and affordable plan voters were assured the agency would implement.

When faced with problems governing boards usually look at external factors, such as inflation, COVID, or shifts in Federal policy, but those things do not explain the Board’s failures to address fundamental problems with the system plan that have become glaringly obvious. To ensure the “enterprise initiative” critically examines the causes of Sound Transit’s problems and honestly evaluates changes to the system plan, the Board must avoid the agency’s in-bred planning process and involve transportation and project finance experts from outside the agency. The Puget Sound region can’t afford a $150 billion dollar mistake.