“I find more and more that dependency from [upon] the will of others is always some diminution of human happiness, principally to a man accustom’d to follow his own will uncontrolled.”

– Jan Ingenhousz to Ben Franklin, 1777

During the two weeks since Americans celebrated the 249th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, political discourse in the United States has been peppered with angry denouncements of any effort to increase the number of Americans who live independently from the government.

When Gov. Kelly Ayotte proposed and Republican legislators approved small premium payments for some Medicaid recipients, they were denounced as cruel, even though Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York already collect premiums.

Federal changes to Medicaid eligibility have been similarly denounced, even though the changes involve work requirements and screening out ineligible individuals, and Medicaid spending continues to grow over the next decade.

Even the ending of taxpayer subsidies for public broadcasting was met with dire predictions of, at best, increased ignorance, and at worst, death (not just for Big Bird). How will rural Americans get weather alerts if Congress doesn’t subsidize left-leaning urban News programming and Metropolitan Opera rebroadcasts?

Every year, progressive New Hampshire legislators push to have all eligible students automatically enrolled in the government-subsidized lunch program—even if their families don’t want them to participate.

Behind every effort to maximize the number of Americans dependent on government aid is the absence of two limiting principles. Both of these principles guide the conservative approach to government while going entirely missing from progressive policy advocacy.

The first limiting principle is the understanding that dependence on government is bad for individuals.

The effort to enroll as many Americans as possible in as many government programs as possible—and keep them there—admits no suggestion or even hint that humans enjoy better, more fulfilling lives when they have the satisfaction of engaging in meaningful work that supports themselves and their families.

The superiority of self-sufficiency over dependence is an American value older than the republic. Ben Franklin expressed the view in 1768 in an essay called “On the Laboring Poor.”

Laws providing for government-ordered and funded poverty relief date to colonial times. From the beginning, these laws have struggled to strike a balance between generosity and available funds (as this essay on Massachusetts poor laws shows).

That tension between the charitable impulse and available funds remains, even in Massachusetts, where demand for guaranteed shelter continues to outstrip funding, leading the state to restrict access.

What’s relatively new is not this tension between heart and head, but the increasingly loud insistence that there are no tensions and no downsides. Many Americans now believe that public assistance is not a regrettable short-term necessity, but an unmitigated good. They no longer recognize self-sufficiency as a worthwhile goal.

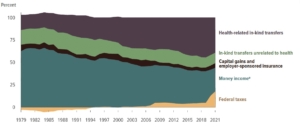

In 1979, Americans with incomes below the federal poverty line earned 62% of their income themselves, according to Congressional Budget Office data. By 2021, those numbers had exactly reversed, and Americans with incomes below the poverty line earned just 26% of their income. Most of the rest came from government aid. (See CBO chart below.)

This development ought to be deeply concerning to all Americans. We should want to help our fellow citizens stand on their own two feet, not lean on the rest of us.

When the corrosive effects of dependence are no longer recognized, then only one limiting principle remains: the availability of government funds.

Activists attempt to overcome this principle by simply asserting that “the rich” or “billionaires” can be ceaselessly milked.

They can’t, though. Forbes reports that the world’s 3,028 billionaires have a combined net worth of $16.1 trillion. That’s not even half the U.S. debt of $36.6 trillion (and growing).

The federal government runs a nearly $2 trillion annual deficit on $6.75 trillion in annual spending. The confiscated wealth of every billionaire on the planet could either cut the federal debt by 44% or pay for about 2.4 years’ worth of federal spending, but not both.

Never mind that the same activists insist that the federal and the state governments all milk the same wealthy individuals to fund ever-increasing government services.

New Hampshire expanded Medicaid in 2014 to able-bodied adults ages 19-64 who made up to 138% of the federal poverty level. Today, that expansion population accounts for 34% of New Hampshire’s Medicaid enrollees, the second-highest percentage in New England. (Vermont’s is 39%.)

Today, 181,000 Granite Staters are enrolled in Medicaid, or about 13% of the state population, though only 7.2% of the population lives below the federal poverty level. Even if one grants that this is a short-term good, shrinking that portion should be a long-term goal. Instead, every proposed reduction is met with vehement opposition to removing anyone from any portion of the program for any reason.

New Hampshire in 2022 spent $9,245 per Medicaid recipient, slightly above the U.S, average of $9,108. The state with the lowest poverty rate in the nation probably shouldn’t have an above-average per-recipient Medicaid spending rate.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid’s performance when it comes to providing recipients with access to care is precisely the same as private insurance. Eighty-five percent of adult participants in either form of insurance saw a doctor in the past year.

So why not try to move as many people as possible off of Medicaid and onto private insurance?

The only reason to object to such an effort is to maximize the number of people dependent on government.

In 1997, President Clinton proposed capping the amount of Medicaid spending on a per-capita basis, which would limit the growth of the program. Today, progressives oppose any limits to either eligibility or spending on any government program as a matter of course. (The only exception is Education Freedom Accounts, which progressives view as a threat to government-operated schools.)

This is true even if reducing spending on one program could free up spending for another. But when you believe that money is limitless, why accept any cuts anywhere?

The Congressional Budget Office projects that even after the One Big Beautiful Bill’s eligibility adjustments, Medicaid spending will exceed $800 billion in 2034, four times what it cost in 2000, after adjusting for inflation, as the Manhattan Institute’s Judge Glock has pointed out. And yet the eligibility reductions were portrayed as just shy of mass executions.

Portsmouth this week rejected a proposal to give residents 15 minutes’ worth of free parking downtown. Council members thought it would cost too much. Like it or not, at every level of government, resources are limited.

That alone is reason enough to insist that programs and services operate as efficiently as possible, and that only the most needy receive assistance. Every dime that is saved can be returned to taxpayers or spent on a higher priority.

Activists who oppose any limitations on eligibility or spending for government programs get the lion’s share of media attention. But most Americans (64%) support removing ineligible recipients from Medicaid rolls, and more than 80% support requiring recipients to work at least 80 hours a month.

That should be a reality check on the media’s breathless, activist-driven coverage. It would be instructive if reporters would ever think to ask the activists who treat any reduction to the rate of growth of any government program as the moral equivalent of genocide what limits they would put on enrollment or spending. Maybe then we could have a conversation about where–rather than whether–to draw lines.