- Duke’s latest resource plan filing shows how unreliable its planned new solar capacity is relative to new nuclear and natural gas capacity

- The plan shows that natural gas is roughly twice as productive as solar, while nuclear is nearly four times as productive as solar

- Solar’s intermittency is why it’s much less productive than coal, gas, and especially nuclear, and also why Duke plans to build so much more new solar capacity as opposed to gas and nuclear

Duke Energy’s latest Carolinas Resource Plan filing with the North Carolina Utilities Commission (NCUC) provides a glimpse into the productivity expected from the different sources of electricity it plans to add. Unfortunately, the source Duke plans to build the most capacity of is also the one it expects the least productivity from.

As noted in the previous brief, under Duke’s plan, North Carolina’s resource mix would increase by nearly 30,000 MW from 2026 to 2040 while retiring 8,445 MW of coal capacity. Nuclear capacity as well as natural gas combined cycle (CC) and combustion turbine (CT) capacity would increase by 59 percent. Solar capacity, however, would almost quadruple.

Unfortunately, the source Duke plans to build the most capacity of is also the one it expects the least productivity from.

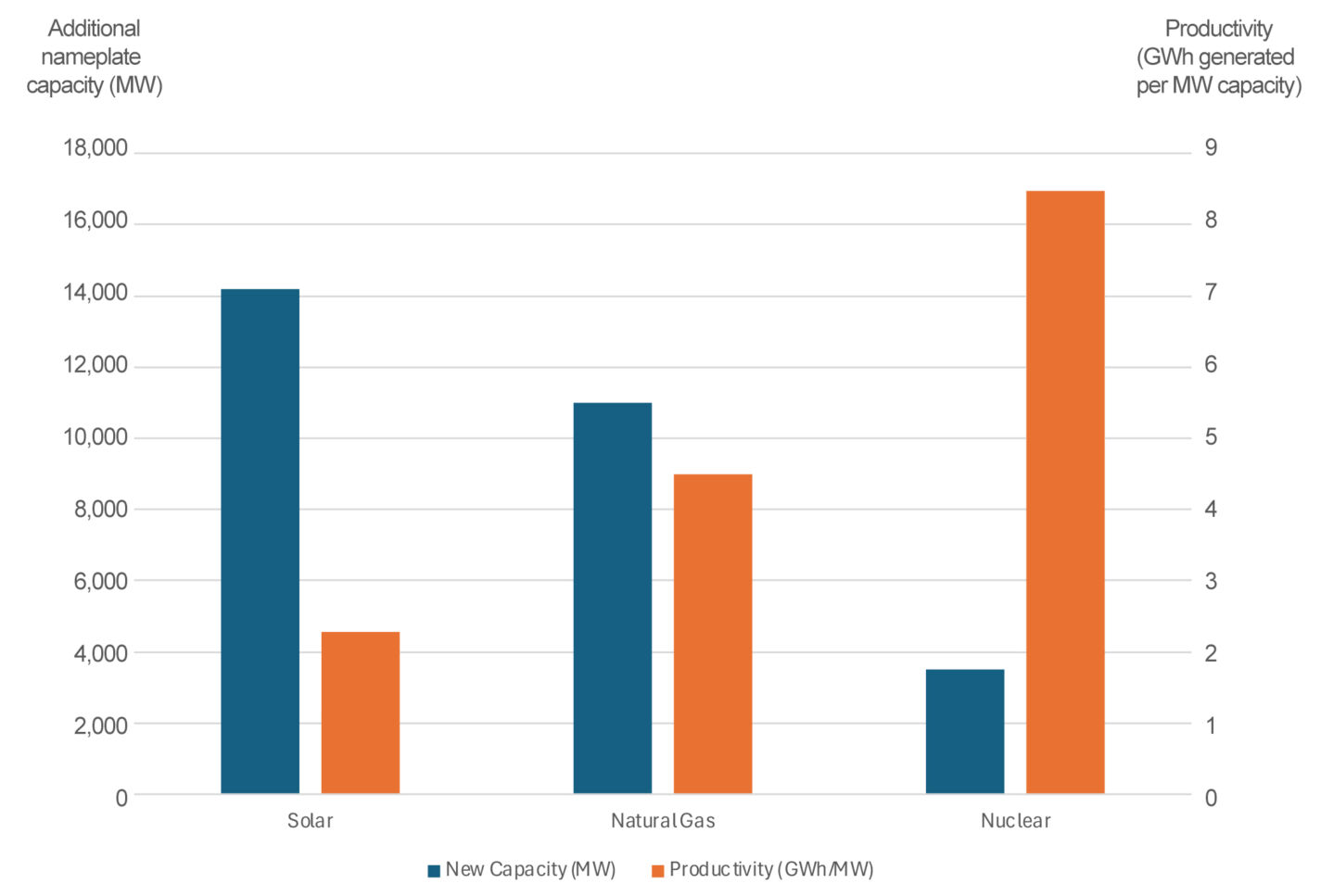

Duke’s estimates show, however, that the new natural gas capacity would be roughly twice as productive as the new solar capacity, while the new nuclear capacity would be nearly four times as productive as the new solar.

Different sources of power, different levels of productivity

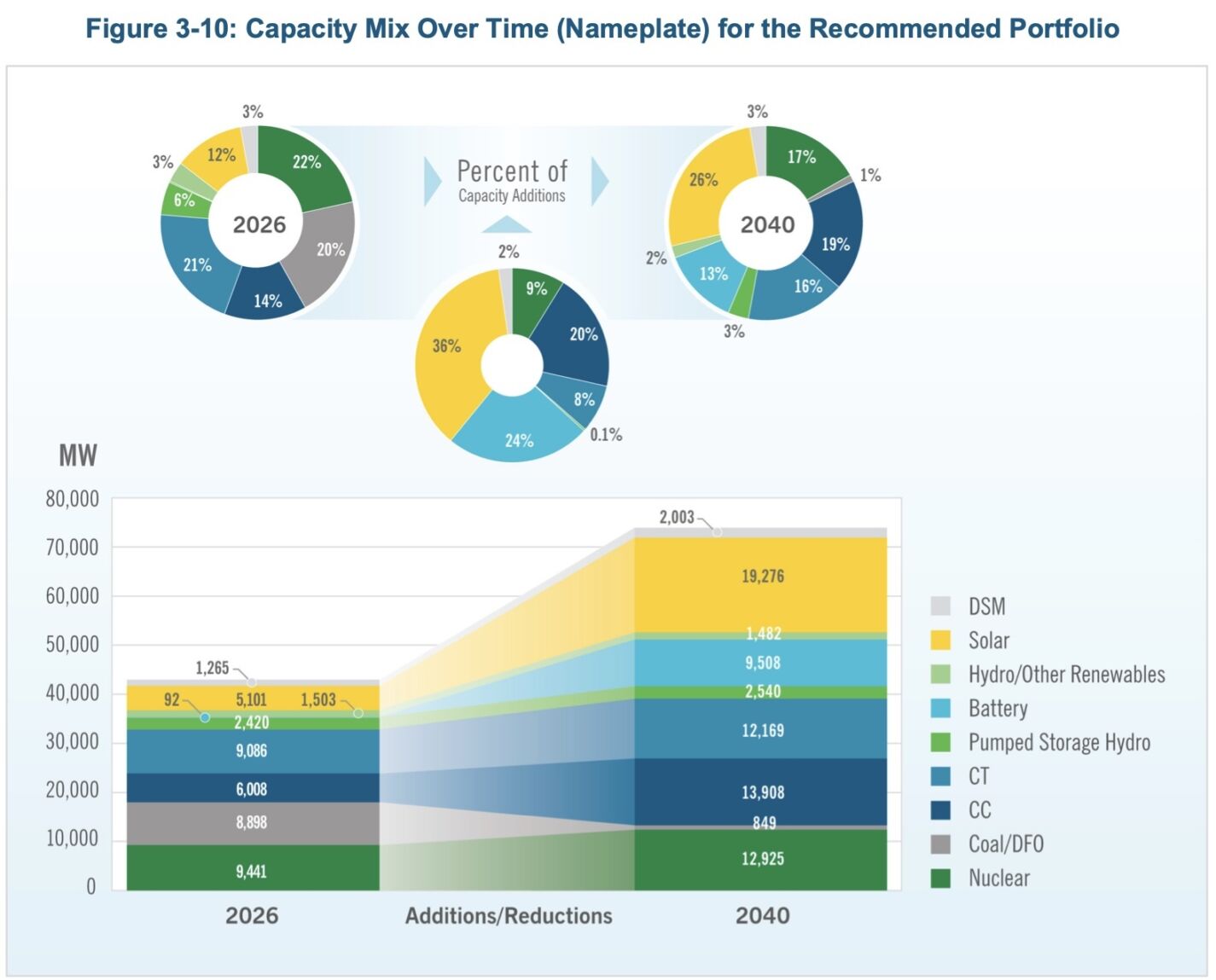

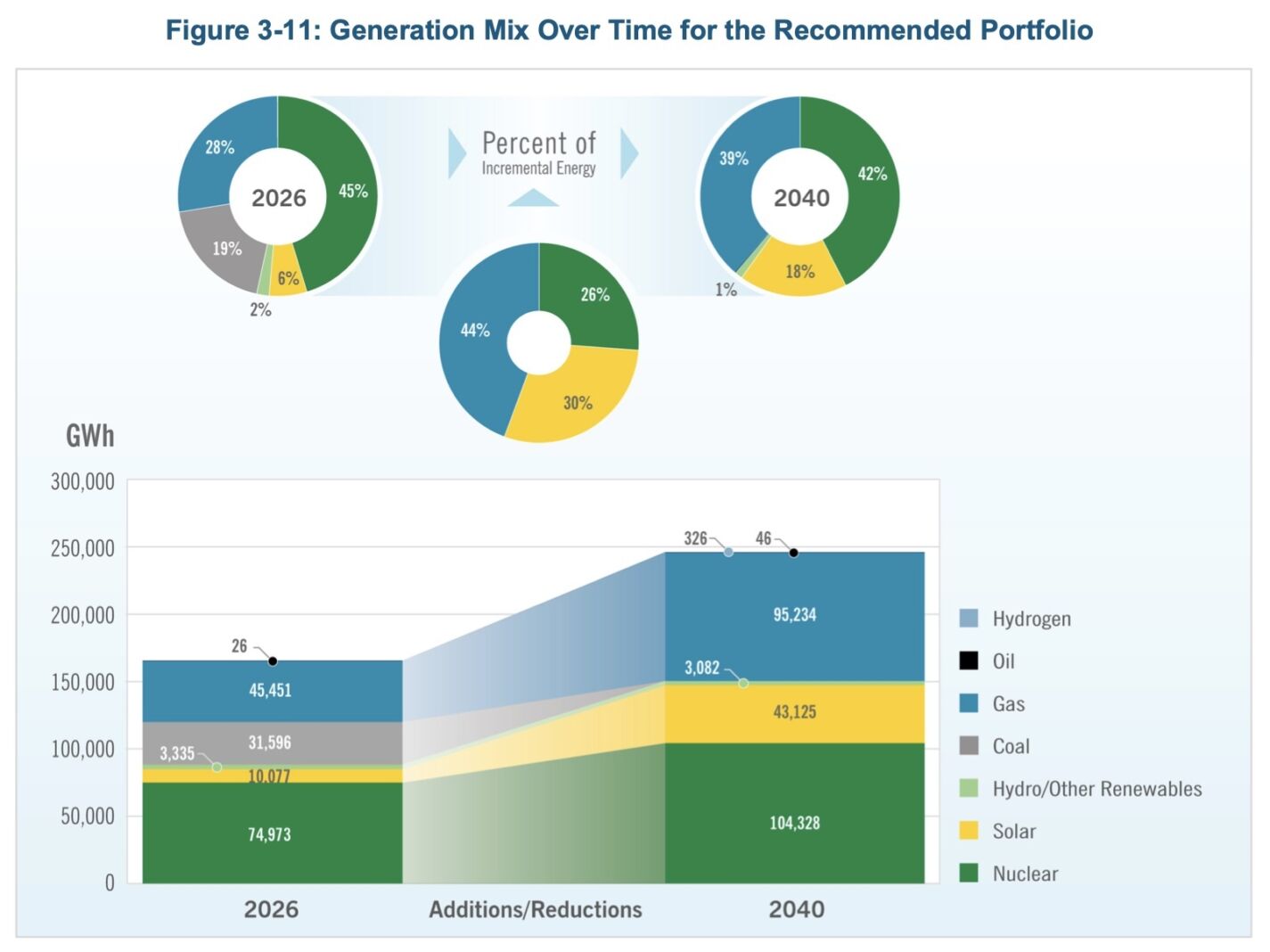

Figure 3-10 of Duke’s filing (see below) shows how North Carolina’s nameplate capacity mix (in MW) changes from 2026 to 2040, and Figure 3-11 shows how North Carolina’s generation mix (in gigawatt-hours, or GWh) changes during that time.

Source: Duke Energy, Carolinas Resource Plan 2025

A cursory glance at the 2040 pie graphs in the two figures reveals that while more than one-fourth (26 percent) of the capacity mix in 2040 will be solar, only about one-sixth (18 percent) of the generation will come from solar. In contrast, only one-sixth (17 percent) of the capacity mix will be nuclear, while the plurality (42 percent) of generation will come from nuclear.

There will be far more solar capacity (more than 19,000 MW) on the grid compared with nuclear (almost 13,000 MW), but nuclear will be producing far more than solar (more than 104,000 GWh vs. more than 43,000).

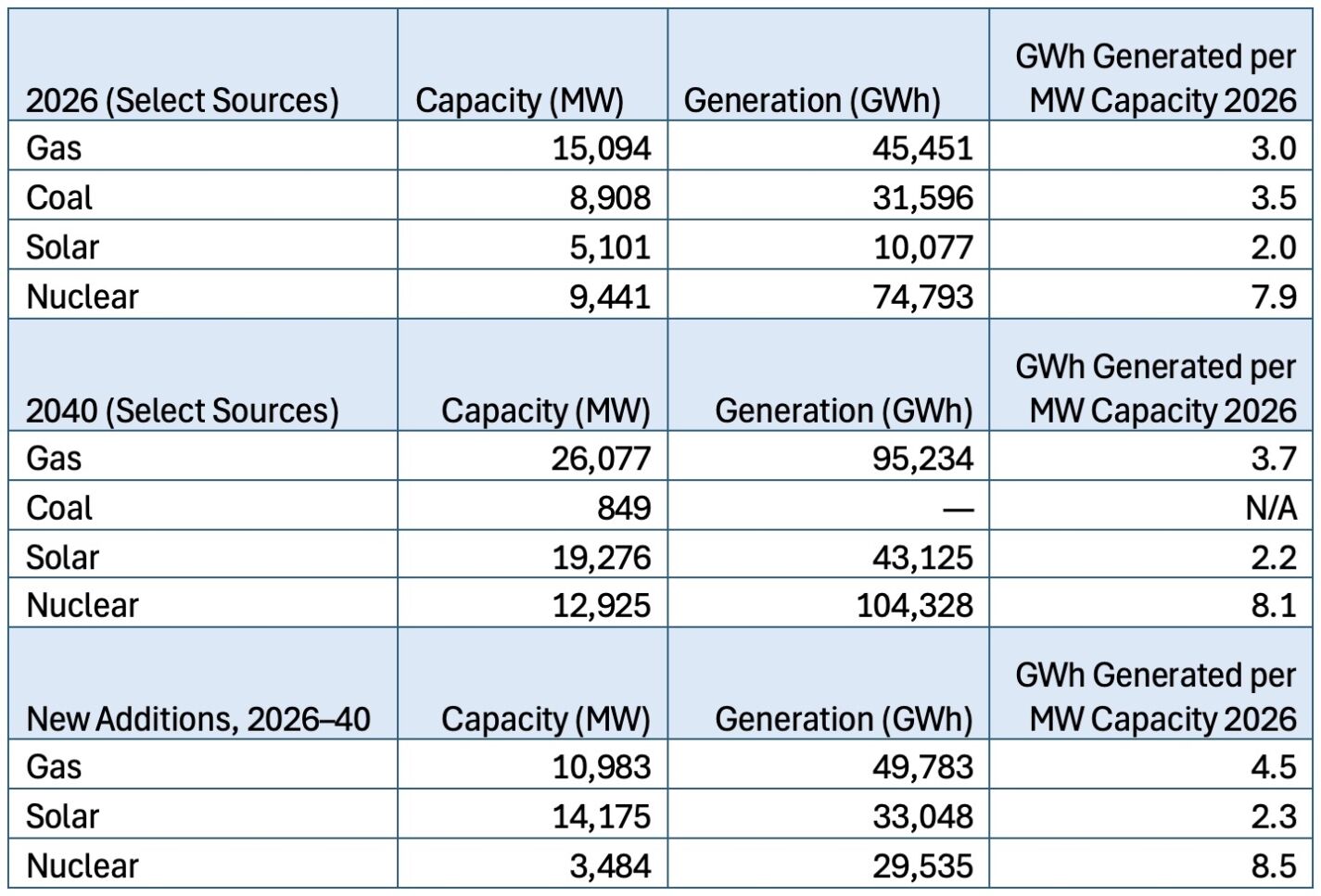

This disparity merits a closer look, which reveals the gulf in productivity mentioned above. The following tables and graph break down the productivity of solar, coal, natural gas, and nuclear in terms of GWh generated per MW capacity. It does so for 2026, for 2040, and also for the new capacity added between 2026 and 2040.

Carolinas Carbon Plan 2025: Electricity Productivity by Source, 2026 to 2040

New Solar, Natural Gas, and Nuclear Capacity: How Much Is Planned by 2040 vs. How Productive Each Source Is Expected to Be

Source: Duke Energy, Carolinas Resource Plan 2025 and author’s calculations

Several things are evident from those charts:

- Nuclear is far and away the most productive source on the grid

- Retiring coal capacity means retiring the second-most productive source per 2026 numbers

- Solar is the least productive source

- Nevertheless, solar is also the source with the most capacity added

- The new solar capacity will be about half as productive as new natural gas — and only about a fourth as productive as new nuclear

Why, though? Isn’t all generating capacity the same?

Nameplate capacity vs. actual productivity

The answer is no, and it’s hinted at in Duke Figure 3-10’s use of the parenthetical “Nameplate” in its title. Nameplate capacity is not the same as power generation, and it differs significantly according to the type of power plant. As explained here, nameplate capacity is “the most electricity production that can be expected from a generating unit at any point in time.”

Here is an illustration: When Strata Solar applied to the NCUC in 2012 to build a 5 MW solar facility on former Gov. Roy Cooper’s Nash County land, the company noted in its application that “Solar is an intermittent energy source, and therefore the maximum dependable capacity is 0 MW.” Its nameplate capacity was 5 MW, but as with all solar facilities, its generation at any moment in time depends entirely upon the time of year, the time of day, and the weather (which is what the application means by “intermittent”). It might occasionally reach 5 MW, but it could very well be at 0 MW.

Solar’s intermittency is why it’s much less productive than coal, gas, and especially nuclear. It’s also why Duke has to build so much new solar capacity — to make up for its unreliability given that the Carbon Plan law still requires the grid to achieve (rather than aspire to) “carbon neutrality” by 2050.

In our 2022 analysis of Duke’s initial Carbon Plan proposal, the John Locke Foundation’s Center for Food, Power, and Life warned the NCUC of this problem of overbuilding solar:

[M]any wind and solar advocates argue that it is better to overbuild renewables, often by a factor of five to eight compared with the dispatchable thermal capacity on the grid, to meet peak demand during periods of low wind and solar output. These intermittent resources would then be curtailed when wind and solar output improves. … This “overbuilding” and curtailing vastly increases the amount of installed capacity needed on the grid to meet electricity demand during periods of low wind and solar output.

Since natural gas and nuclear are highly reliable resources, their productivity doesn’t require building nearly as much nameplate capacity. In terms of productivity, using numbers reported by Duke Energy, the productivity factor for nuclear was 100.3 percent; for natural gas, 80.4 percent; but for solar, an average of 3.5 percent in the winter and 45.4 percent in the summer.

Overbuilding solar facilities not only adds to electricity bills from the facilities themselves but also from all the new transmission infrastructure they require. It also would take over a tremendous amount of the state’s already endangered farmland.

If the Carbon Plan law were amended to make its carbon neutrality requirement a goal instead, secondary to the needs of consumers for reliable and least-cost electricity, it would allow Duke in future resource plans to showcase more natural gas and nuclear capacity, which would create significant savings for ratepayers.