- A growing proportion of Americans, especially young adults, have a “favorable” view of socialism

- The very first settlements in America, Jamestown and Plymouth, adopted socialist precepts and wound up suffering socialist consequences: laziness, famine, and death

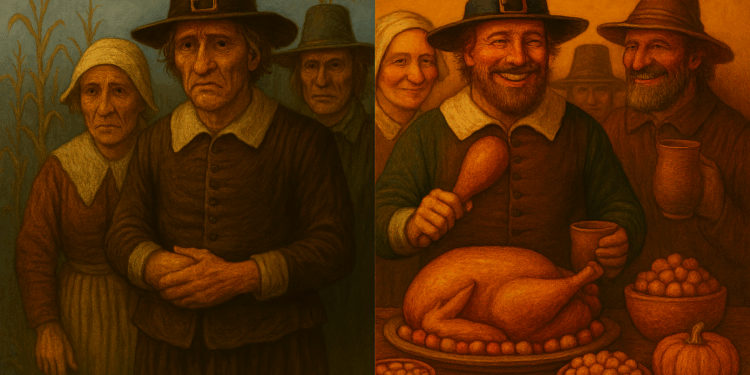

- Out of dire need, they switched to property ownership and free enterprise and quickly enjoyed abundance, leading at Plymouth to the first Thanksgiving celebration

Socialism seems to be polling higher in America, especially among younger Americans. A recent Cato survey found that 62 percent of respondents aged 18 to 29 held a “favorable view” of socialism, while Rasmussen Reports found that 51 percent of voters aged 18 to 39 would like to see a democratic socialist win the presidential election. Results in recent polls of Americans of all ages varied widely, from 18 percent (NBC News) to one-third (YouGov and The Economist) to 39 percent (Gallup) with a positive view of socialism.

The polls don’t define socialism, so it’s possible that many respondents simply don’t know exactly what it is they’re professing a favorable opinion of. For most of us, socialism brings to mind false promises, privation, fear, tyranny, and despair. For others, perhaps “socialism” sounds to them like being social, which is nice. Unfortunately, socialists handed the reins of power invariably disabuse their subjects of any mistaken notions of socialism once they can no longer do anything about it.

Early American settlers quickly discerned the true consequences of socialism, most of them fatally. In fact, the story of first Thanksgiving is bound up with the move from socialism to free enterprise.

Jamestown: From starving to surplus

Socialism nearly destroyed the first permanent English settlement in America, the colony at Jamestown, established in 1607. As Robert C. Ellickson of Yale Law School observed in 1993, “land was held as a collective asset” and each settler was “guaranteed an equal share of the common output regardless of the amount of work personally contributed.”

Everyone shared the land and shared the produce of the land. What could go wrong?

Plenty. Jamestown socialism didn’t give rise to a happy community of families pulling together for the greater good; instead, it produced a shocking laziness even as people starved.

Ellickson wrote:

To the puzzlement of historians, the starving settlers shirked from catching fish and growing food. The most enduring image of Jamestown dates from May 1611, when Sir Thomas Dale found the inhabitants at “their daily and usuall workes, bowling in the streetes.”

If this needs more context: In 1609, the colony had suffered a particularly cruel famine that killed most of the colony’s population, which fell from 500 to only 60. Two years later, the “daily and usual work” in Jamestown was playing street ball. No wonder historians were puzzled.

When Jamestown abandoned socialism and moved to property rights and privatized agriculture, the results were immediate — and resoundingly positive. What happened was, Jamestown’s governor, Sir Thomas Dale, began assigning three-acre plots to the settlers in 1614. Captain John Smith wrote that productivity improved “at least sevenfold”:

When our people were fed out of the common store, and laboured jointly together, glad was he could slip from his labour, or slumber over his taske he cared not how, nay, the most honest among them would hardly take so much true paines in a weeke, as now for themselves they will doe in a day, neither cared they for the increase, presuming that howsoever the harvest prospered, the generall store must maintaine them, so that wee reaped not so much Corne from the labours of thirtie, as now three or foure doe provide for themselves. To prevent which, Sir Thomas Dale hath allotted every man three Acres of cleare ground …. [Emphasis added.]

What Smith observed, in other words, was that when people “shared the land and shared the produce of the land,” people also shared an incentive not to work. They were “glad” to sneak away, sleep in, and simply not work as hard as they could. Nobody had any ownership in work, but each had ownership in leisure. Thinking that others were putting in the work to feed them, they expected to be “paid” for goofing off.

When people had ownership of their own harvests, they were compensated for how much work they put in, and they were further incentivized to work when they realized they could trade any surplus they produced to create greater wealth for themselves and their families.

Ellickson explained:

The “Great Charter of 1619” capped Jamestown’s march toward decentralized agriculture. Although the Great Charter kept some lands in common ownership, its greatness lay in its broad distribution of entitlements to establish private farms.

Agricultural productivity unquestionably improved at Jamestown as lands were privatized. By around 1620, farmers were energetically growing tobacco, a profitable export crop.

Going from socialism to private property and free enterprise, Jamestown saw its people transform from starvelings lazing away in the streets to well-fed entrepreneurs “energetically” growing profitable crops.

Plymouth: From famine to Thanksgiving

Jamestown’s failed experiment with socialism was duplicated a few short years later by the Pilgrim setters of Plymouth. They, too, set up their land ownership to be fair and equal in which everyone shared in the work and shared the produce. Once again, people realized that avoiding work yielded the same reward as working hard.

Under the banner of equality for everyone, the settlers of Plymouth suffered a famine lasting two years that threatened to stretch into three or more. Half the settlers died.

As at Jamestown, the settlers turned in desperation away from socialism to private enterprise. As Gov. William Bradford explained, they moved to “trust to themselves” and “assigned to every family a parcel of land, according to the proportion of their number,” for their own use instead.

As at Jamestown, success was immediate and overwhelming. Bradford wrote (emphasis added):

This had a very good success; for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been by any means the Governor or any other could use, and saved him a great deal of trouble, and gave far better content. … By this time harvest was come, and instead of famine, now God gave them plenty, and the face of things was changed, to the rejoicing of the hearts of many, for which they blessed God.

The first Thanksgiving was held that year in 1623.