Surging child care prices have grabbed the media’s attention here in New Hampshire, and rightly so. The price of full-time care in a licensed center “jumped 48 percent between 2013 and 2023,” landing at nearly $32,000 a year, according to an analysis last year by the Carsey School of Public Policy at UNH.

Child care prices have been rising for years, drawing increasing media interest. Data analysts have noted that there’s a large gap between the demand for child care and the number of available spaces. In 2024, nhchilddata.org estimated that 54,000 children under age six needed child care, while only 45,610 spaces were available, leaving 8,390 kids without a spot. And that doesn’t include the children over age six.

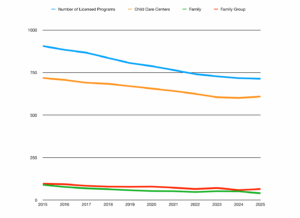

There’s been a steady decline in the number of all types of child care providers in New Hampshire going back at least a decade.

This gap between supply and demand ought to ring a bell in the minds of reporters.

Every news organization in New Hampshire has covered the state’s housing shortage for years and years. Since the Josiah Bartlett Center published our landmark housing study in 2021, it’s become widely accepted by economists, industry analysts, academics, lawmakers and even journalists that the primary factor contributing to the state’s housing shortage is excessive government regulation.

When another industry pops up with a large gap between demand and supply, leaving thousands of Granite Staters desperate for someone to take their money in exchange for a critical service that’s in short supply, something ought to click inside newsrooms around the state.

And yet…

Media coverage of the rising costs of child care is very similar to media coverage of the rising costs of housing before 2021. Instead of asking whether government might be intervening too much in the market, leading to a constrained supply, the narrative tends to be one of insufficient government action. State subsidies aren’t generous enough, or the minimum wage isn’t high enough, activists tell reporters, their assertions unchallenged. If only the government would spend or regulate more, the narrative goes, then thousands would find relief from these magically rising prices.

That framing used to characterize coverage of the state’s housing shortage. Activists ran to the media to demand that the state raise the minimum wage and spend more to subsidize “affordable housing.” The media dutifully reported that more people could afford housing if the government would only spend and regulate more.

Today, a few of those stories still appear. But the overwhelming consensus, formed by a lot of good research, is that excessive government intervention in the market created a housing shortage, and the shortage spiked prices.

The media should be asking whether a similar situation exists in child care.

A recent headline suggested that the question had occurred to someone. The New Hampshire Bulletin did a few big stories on child care costs this month. One of the stories bore this headline:

“With crushing costs and too-few slots, child care strain grows for New Hampshire families.”

Finally, a story addressing the connection between supply and costs!

Alas, no.

The story did acknowledge the existence of regulatory burdens—on applicants for state subsidies. It reported on a state pilot program “to cut down on administrative burdens” for families who apply for a state child care scholarship. There was nothing on why costs might be rising in the first place.

We haven’t done a study of New Hampshire’s child care industry to see if there’s a significant relationship between regulations and the supply and cost of care here. (If you know anyone who’d like to fund such a study, please reach out at [email protected].) But given the lesson of the state’s housing prices, shouldn’t reporters be asking?

New Hampshire’s child care regulations are among the most burdensome in the country, according to an analysis published last fall by West Virginia University’s John Chambers College of Business and Economics.

New Hampshire’s child care regulations ranked 35th in the country, with a lower ranking meaning heavier regulations. We placed higher than all other New England states, but our regulatory burden was rated heavier than in many states with more activist governments, such as Delaware, Illinois, Michigan, Hawaii and California.

As with housing, there’s a documented relationship between the regulatory burden in child care an the availability and cost of services. For example:

A 2017 study in Applied Economics found that “regulation intended to improve quality often focuses on easily observable measures of the care environment that do not necessarily affect the quality of care but that do increase the cost. Thus, we find that the regulatory environment could be improved by eliminating costly measures that do not affect quality of care.”

A 2011 study in the American Economic Review found that “the imposition of regulations reduces the number of center-based child care establishments, especially in lower income markets. However, such regulations increase the quality of services provided, especially in higher income areas. Thus, there are winners and losers from the regulation of child care services.”

The Child Care Regulation Index that ranked New Hampshire 35th in regulatory burden shows that a lot of state regulations (including in New Hampshire) are focused on structural requirements such as group size and child-staff ratios.

Yet those regulations have been shown to have the lowest positive effects. A 1997 study, “The production of quality in child care centers,” found that “group size, child-staff ratio, and staff education and training have only small impacts on the quality of care provided.”

A 2010 follow-up study by the same author found again that “(t)he empirical results indicate that group size has small and statistically insignificant effects on child-care quality. A higher staff-child ratio appears to have beneficial effects on child-care quality when unobserved differences across centers are not accounted for. These effects become much smaller when unobserved differences are accounted for. The effects of teacher education and training are also generally not robust, but some measures of education and training have quantitatively and statistically significant effects even accounting for unobserved differences across centers.”

It’s possible, probably likely, that New Hampshire’s regulations are imposing costly burdens such as an increase in staffing—which lowers pay for staffers—without producing corresponding increases in quality.

A Carsey School of Public Policy analysis last year found that between “2017 and 2024, New Hampshire’s licensed child care capacity increased by 5.6 percent, while its count of licensed providers shrunk by 13 percent. This mismatch is attributable to the greater rate of closure among home-based providers, part of a larger trend in New Hampshire and nationwide.”

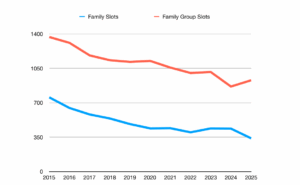

State data show a sharp decline in the number of spots available in family child care homes (residential care with up to six pre-school and three school-age children) and family group care homes (residential care for 7-12 preschool children and up to five school-age children in the last decade.

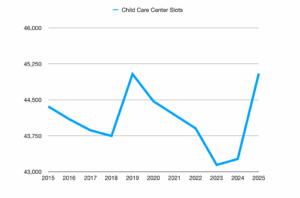

At the same time, the number of slots in licensed child care centers declined, then rebounded.

There are surely many reasons for this trend. What could account for an industry seeing small providers close and larger providers move in to take that market share? Labor costs, low profit margins and worker shortages are three common factors. Another often is that larger providers can more easily absorb higher regulatory and labor costs.

Regarding family child care homes, another factor could be fragmented local family and social networks. Trusting a neighbor with your children requires trusting–and knowing–your neighbor. Most Granite Staters were born out-of-state. Maybe having shallower roots in a community leads parents to prefer larger day care centers over the mother or grandmother down the street.

Looking into the reasons for the child care shortage, including any possible regulatory factors, should be top of mind for reporters and analysts, not only because of the obvious surface similarity to the state’s housing issue, but also because legislators just last year felt the need to intervene and pass a bill to prohibit the common practice of local governments banning home-based child care as an allowed use in residential districts.

There we had a case of perfect overlap between housing and child care regulations, with local governments using zoning powers to prohibit the the provision of residential child care services—the very services that shrank rapidly in the last decade.

This is a topic ripe for research, investigation and reporting. Solving the supply shortage will be harder if policymakers and the media treat it like housing years ago and assume that the only solution is more government spending and intervention.