- Citing classified information, the U.S. Department of the Interior last month halted five offshore wind projects under construction, including Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind

- Offshore wind facilities pose well-known risks to national security by causing radar clutter and hindering military training

- Speculative national security risks include swarm drone attacks, foreign-made components placed on critical energy infrastructure, and attacks launched from autonomous submarines

Citing national security risks, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) announced on Dec. 22, 2025, that it was pausing the leases “for all large-scale offshore wind projects under construction in the United States.” Because the projects affected are already under construction, this halt is different from President Donald Trump’s earlier directive halting government leasing of offshore wind projects.

The projects affected are Vineyard Wind 1 (Massachusetts), Revolution Wind (Rhode Island), Sunrise Wind and Empire Wind 1 (New York), and Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind (CVOW), the country’s largest offshore wind project. CVOW was set to begin operation at the end of this year. So far, Revolution Wind, Empire Wind, and CVOW have obtained temporary injunctions in federal courts against the DOI’s order.

A DOI press release said that the national security risks were “identified by the Department of War in recently completed classified reports.”

Known risks of offshore wind facilities to national security and defense

DOI also cited long-known findings from unclassified reports that “the movement of massive turbine blades and the highly reflective towers create radar interference called ‘clutter.’”

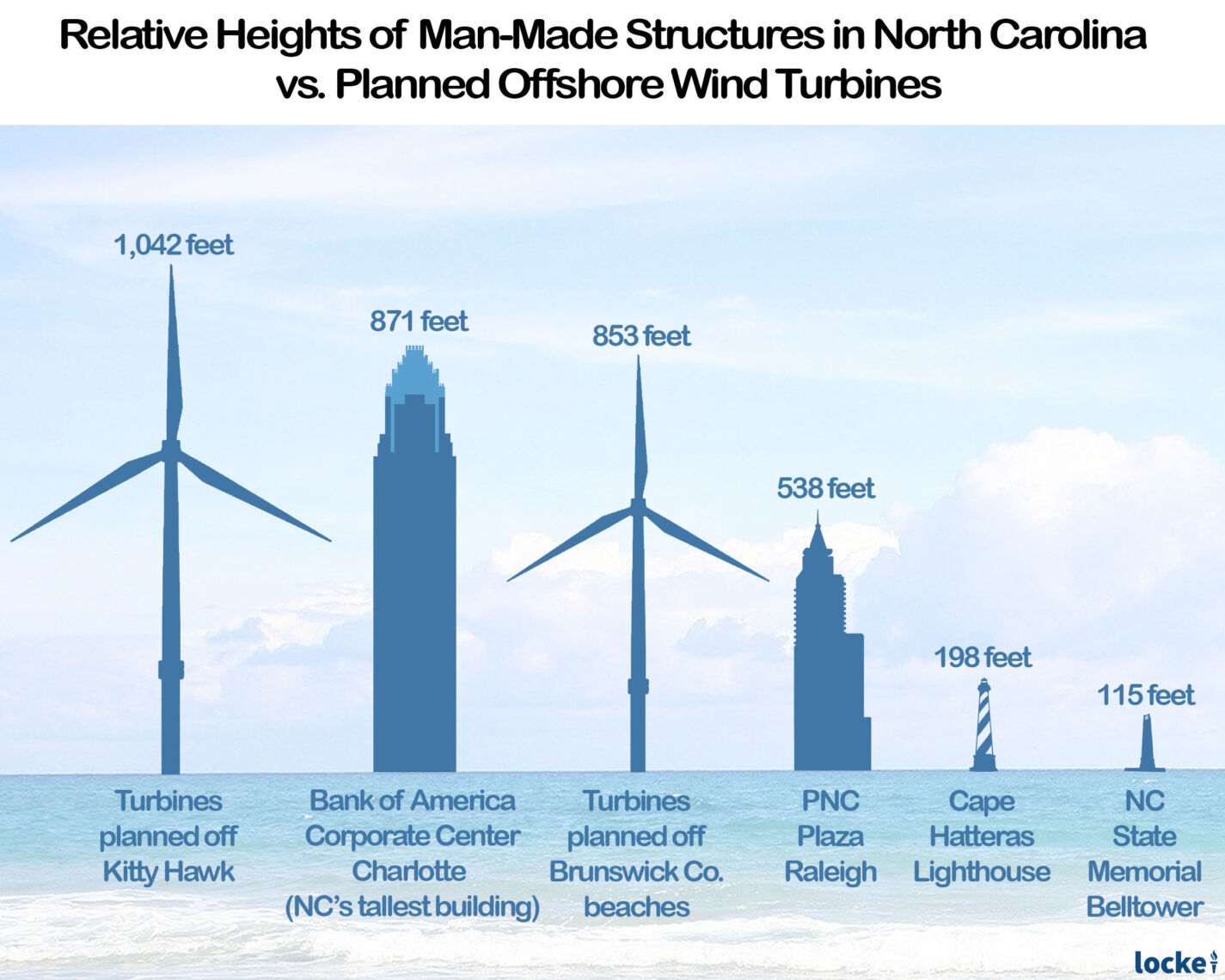

The public generally does not understand how enormous offshore wind turbines are. The ones that had been under consideration for North Carolina would have been the tallest manmade structures in the state.

Large numbers of such enormous structures would have been arrayed across huge areas. The Kitty Hawk project would have featured 170 turbines over 193 square miles. The Carolina Long Bay project off the coast of Bald Head Island and the Brunswick County beaches would have featured 122 turbines over 172 square miles.

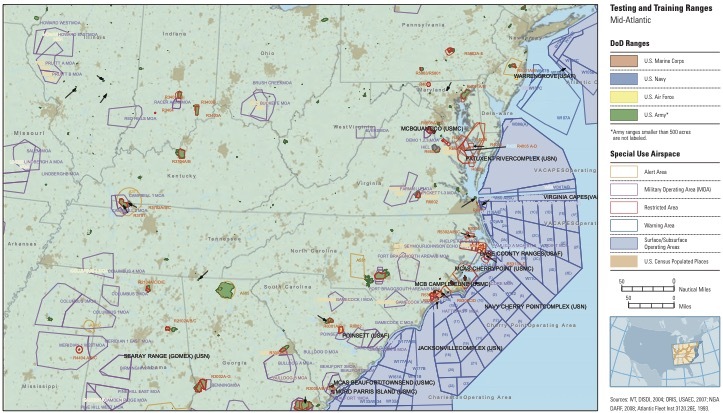

The Pentagon had alerted the Biden administration that the Kitty Hawk project along with five other projects off the coasts of Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware would be “highly problematic” and conflict with military operations:

Four of the six areas, including the Kitty Hawk project, were highlighted in red, signifying areas the Pentagon considered “highest priority” areas. It is in these areas, including the Kitty Hawk project, “the Pentagon would be unable to continue its mission as currently conducted in the space.”

Among other problems, the Kitty Hawk project would have severely disrupted fighter jet training using the Dare County Bombing Range, a large training range that meets “F-15E training requirements of not only the 4th Fighter Wing at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, N.C., but also the Navy and Marine Corps.”

Military testing and training ranges, mid-Atlantic states

Source: U.S. Department of War (Department of Defense)

The Carolina Long Bay project would have impacted training missions by the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps, according to public comments to the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management by Colonel Quaid H. Quadri, Jr., commander of the 169th Fighter Wing, South Carolina Air National Guard. Quadri noted that the project would adversely impact “the only local airspace that is approved for supersonic flight and has the range to execute air to air tactics” and would “reduce the area available to conduct low altitude training.”

Quadri also warned that such a large area of radar clutter would “hinder [Air Traffic Control]’s ability to safely control aircraft and degrade critical and uniquely available combat training.”

Radar clutter also disrupts marine vessel radar, creating higher risks of open-seas collisions and hindering search-and-rescue operations, according to a February 2022 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Worse, the disruptions are worse when the wind is blowing. The report also found that there is “no simple modification” that could allow marine vessel radar to operate in “the complex environments of a fully populated continental shelf wind farm.”

Speculation over what new risks have been identified

The new risks are in classified reports and therefore not disclosed to the public. It has led to speculation over what they could be.

One risk could be that offshore wind facilities’ radar clutter could provide ideal conditions for launching a drone attack. Rep. Chris Smith, R-N.J., told the New York Post that the clutter from offshore turbines could hinder the military from being able to intercept foreign drones. As an example, he cited the government’s inability to stymie the mysterious drone activity in New Jersey in late 2024.

In August 2025, Interior Secretary Doug Burgum had cited the threat of a drone attack in discussing an order to halt construction on Revolution Wind. In an interview with CNN, Burgum mentioned “undersea drones, the new technology,” and the possibility of “a swarm drone attack through a wind farm” to take advantage of radar distortions.

Derrick A. Max of the Thomas Jefferson Institute for Public Policy in Virginia discussed “classified national security concerns involving foreign-made components — undersea cables, turbine electronics, and data systems linked to Chinese suppliers” — used in “critical energy infrastructure” as a potential risk that would be “naïve to ignore.”

David Wojick of CFACT noted that CVOW “lies just off” Naval Station Norfolk, a very inviting military target. The U.S. State Department says that Naval Station Norfolk is “the world’s largest naval station, with the largest concentration of U.S. Navy forces through 75 ships alongside 14 piers and with 134 aircraft and 11 aircraft hangars at the adjacently operated Chambers Field.”

Wojick speculated a threat could be “an autonomous submarine armed with torpedoes or cruise missiles hiding among the giant monopiles,” which would take advantage not of radar interference, but sonar interference. The unmanned sub could be quite small and could even be dropped off in the nearby shipping lanes, Wojick noted. He also mentioned the possibility of a swarm attack from undersea drones.

These issues would be disturbing even if the energy source in question were a reliable, dispatchable source. Offshore wind, however, is neither. It seems to pose more risk than reward. The good news for North Carolina is that Duke Energy announced in August 2025 that it would no longer be pursuing offshore wind energy generation here.