In my earlier op-ed, I argued—drawing on economist Friedrich Hayek—that the Department of Education embodies the fatal flaw of all central planners: the illusion that distant authorities can gather, process, and act on local knowledge better than the people on the ground. Hayek’s central insight is about who should rule; decisions should be pushed down to the most decentralized level, because the people closest to the problem hold the most relevant information.

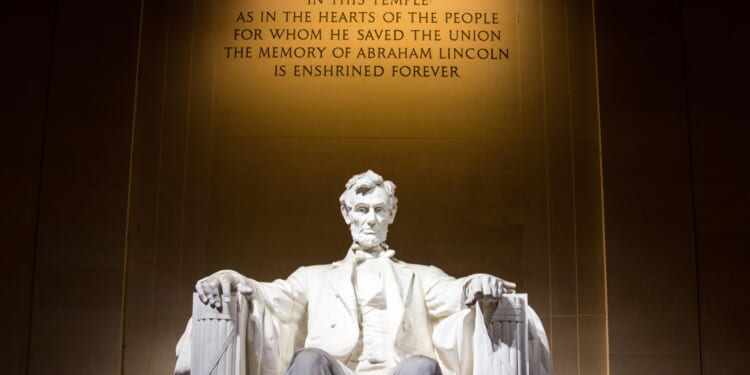

But Hayek’s contribution, while insightful, is incomplete. He asked who should make decisions. Abraham Lincoln asked a better question: To what end should decisions be made?

This is where Lincoln steps into a conversation Hayek never fully addressed and where an older tradition—Aristotle’s political philosophy—helps clarify the difference. Aristotle taught that political analysis cannot stop at identifying whether the one, the few, or the many hold power. The real issue is who holds that power and for whose benefit it is exercised. Government, for Aristotle, must be evaluated not only by the number of rulers, but by the moral purpose of their rule.

His six-fold regime typology—three “correct” and three “deviant”—turns on this single distinction. Kingship, aristocracy, and polity are the forms that govern for the common good. Tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy (as Aristotle used the term) are the corrupt forms that govern for the selfish interests of the rulers. While Aristotle praised polity as the most stable form of government, its defining feature is not merely a strong middle class. The middle class is instrumental because its moderation checks extremes—but the real essence of polity is its mixing of democratic freedom with aristocratic virtue under the rule of law. A true polity blends liberty and excellence, channeling both through institutions that orient rulers toward moral ends.

The stability of the American Constitution rests less on socioeconomic class and more on its moral and institutional architecture—checks and balances, structures that pit “ambition against ambition” while fixing the eyes of rulers and citizens on permanent truths about justice and the common good, truths articulated most clearly in the Declaration of Independence.

For Aristotle, freedom was never the ultimate end of political life. Freedom was the means through which citizens pursue the end: virtue and the common good. That hierarchy echoes through American political thought. George Washington spoke of “ordered liberty,” insisting that freedom must be bounded by moral law and civic duty. A century later, Lincoln understood the American promise as equality of opportunity, a color-blind meritocracy grounded in the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence. Both men believed that politics cannot be morally neutral.

Hayek, like Aristotle, believed in something transcendent; for Hayek, the supreme value was freedom and the dispersion of decision-making to individuals with local knowledge. But where Hayek saw freedom as the end, Aristotle—and Lincoln—insisted that freedom serves something larger. Local knowledge can help us decide how to teach a child; it cannot determine what a republic must teach its citizens about justice, human dignity, or the principles that hold a nation together.

This is the heart of Lincoln’s debate with Stephen Douglas. Douglas insisted that every community should vote slavery “up or down” as it pleased. His doctrine of popular sovereignty treated process as the highest principle. But Douglas was not merely a proceduralist—he was, as Lincoln understood, a moral nihilist. His “don’t care” position on slavery was a positive claim that no truth about justice exists that reason can discover—only will, preference, and power remain.

Lincoln’s reply was a direct rejection of that worldview. The principles of the Declaration, he argued, are “an abstract truth applicable to all men and all times,” and a house divided on that question cannot stand. Majority rule is only legitimate when anchored to transcendent moral standards that no vote can overturn.

Aristotle would have agreed. When a society reduces every question to local preference without a shared moral horizon, it dissolves into factions governed by passion rather than principle. Pure process cannot hold a nation together.

Which brings us back to the Department of Education. The problem is not merely bureaucratic centralization—although that is part of it. The deeper problem is the content now taught: a deliberate repudiation of the Founders’ understanding of equality and natural rights, in favor of historicist, relativist, and increasingly Marxist interpretations of America. A nationalized system that enforces Douglas-style majoritarianism without Lincolnian moral substance cannot sustain the republic. Decentralization is necessary but not sufficient. We also need teachers, textbooks, and curricula that still believe the Declaration is true.

The point is not simply to decide who rules, but to ask the question Lincoln pressed upon the nation: To what end is that power used?