How do you measure the success of a business?

You might look at financial measures such as profits, dividends or share price, industry dominance such as market share, or how well it achieves its mission. A law firm could measure success in client wins, a sports team in championships.

What do all of those measures have in common?

They’re outcomes.

In the public sector, success too often is measured by inputs (e.g. government spending).

Departments, agencies and programs are measured by how much funding they receive and how large their constituencies are.

We mentioned last week the New York Times story that framed enrollment declines as a “crisis” for district public schools. The story never mentioned National Assessment of Educational Progress data which show that fewer than 1/3 of U.S fourth graders and eighth graders are proficient in reading while just 36% of fourth graders and 26 percent of eighth graders are proficient in math.

Those performance outcomes are the real crisis. And they are one contributor to the enrollment decline (though the primary reason is demographic).

But the media share the government’s unfortunate tendency to focus on government inputs, primarily financial, rather than outcomes. Reductions in government subsidies are treated as crises, while unacceptable outcomes are treated as… the fault of insufficient inputs.

It’s far less common to see stories that try to connect regulatory burdens, management decisions and constraints on innovation to outcomes. It’s much easier to measure inputs, even when there’s strong evidence that input levels can’t explain certain outcomes.

The Boston Globe and Union Leader wrote this week about University System of New Hampshire state subsidy cuts, and they’re classic inputs-focused stories. The implication in the stories, which were based on a left-wing think tank report, is that this year’s reductions in USNH state subsidies equal tuition increases. (Though, interestingly, the report didn’t show that this has happened in the past.)

It’s reasonable to assume that a large and sudden cut would be likely to trigger a tuition increase, as appears to have happened this year. But how closely connected are subsidy rates and tuition rates in general?

The simplistic way to frame any discussion of state subsidy cuts is to link them directly to the other best-known revenue source, tuition. But that ignores every other factor that goes into university budgeting.

The USNH Annual Financial Report for 2024 shows that the system had $462 million in grant, contract and service sales revenue, dwarfing the state’s $98 million subsidy. Net tuition and fee revenue (after financial aid) added another $276 million.

The left-leaning Brookings Institution investigated the connection between state subsidies and tuition in a 2018 study. That report found that “declines in state funding are only one of a number of factors that may influence price increases, and these funding declines generally lead to a combination of higher prices, lower spending, and changes in the composition of in-state and out-of-state students enrolled.”

We can see this in New Hampshire.

In 2010, 40% of UNH students were from another state. That year, UNH posted its highest in-state enrollment, 8,667 students (undergraduate and graduate).

Since then, the percentage of out-of-state students rose to 55% in 2022 and 2023. This is one way UNH has raised additional revenue without raising in-state tuition. UNH has also gone through some rounds of budget cutting in recent years, and that is continuing.

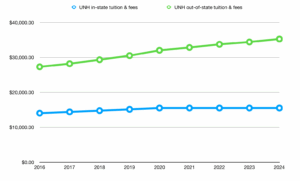

Over the last decade, UNH kept in-state tuition fairly flat while raising out-of-state tuition. So not only did UNH strive to keep in-state tuition low by bringing in a lot more out-of-state students, it raised tuition on those out-of-state students too.

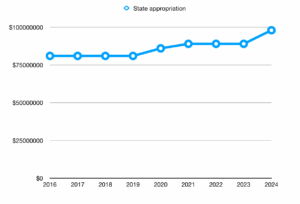

In this same time, state subsidies weren’t cut; they were increased.

When tuition rises as state aid also rises, trend stories linking subsidies and tuition are hard to find. But as soon as state aid is reduced, they appear.

“The university system is very important, but enrollment trends are down so we need to look at ways we can do things differently,” Gov Kelly Ayotte told the Union Leader.

That’s right. Never mentioned in these input-focused stories are system designs that make it harder for institutions to do more with less.

University systems are layered over with mandates and regulations that discourage cost-cutting and innovation. Some of those come from government, but not all.

Have you ever wondered why so many four-year colleges feel interchangeable? A lot of that comes from private accreditors.

Federal funding has been tied to accreditation since the 1950s. The idea was to keep federal money from going to bad schools. But guess what the private accrediting agencies measure?

Inputs.

The input-based accreditation process raises costs and stifles innovation and efficiency.

Reforming college and university accreditation has been an issue in higher education for years. The Biden administration, left-leaning think tanks, right-leaning think tanks and a national advisory committee have suggested reforming accreditation, primarily to focus more on student outcomes.

In June, a consortium of six universities announced the formation of a new accrediting agency, the Commission for Public Higher Education. Unlike existing accrediting agencies that focus on financial and structural inputs, the new commission will focus on student outcomes and academic excellence.

It’s simple to draw a straight line between tuition and state subsidies. But it’s not just simple, it’s simplistic. If universities are locked in to costly models, their ability to cut costs through innovation and efficiency is limited.

Yes, New Hampshire’s state subsidies for its university system are low when comparing us to other states. And yet UNH is continually rated as a top value in higher education (No. 7 in the nation, No. 1 in New England last year).

UNH also ranks 52nd in US News & World Report’s college rankings, tied with Cal State-Long Beach, George Mason, San Diego State, Arizona, Missouri, UT-Knoxville, and University of Texas at Dallas. It ranks above the University of South Carolina, University of Vermont, University of Oklahoma, University of Utah, Oregon State, Colorado State, James Madison and many other well-known and respected universities.

Whether you place a low or high value such rankings, these types of metrics somehow go unmentioned in most stories about USNH state subsidies.

Relatively low state subsidies have forced UNH and USNH to operate relatively leanly, to strive to do more with less within existing regulatory and market constraints. That’s been good for taxpayers, and it’s made our system more efficient than others.

We can debate what the appropriate level of subsidy is. But we should stop getting duped into focusing on this one input to the point that we ignore other vital inputs and all outcomes.