On Jan. 5, 1776, New Hampshire became the first self-governing British colony in North America. That astonishing decision, made 250 years ago this week, deserved a bigger celebration than it received.

After a quarter of a millennium, Americans have become accustomed to thinking that self-government is normal. It isn’t. Achieving it in 1776 was extraordinary.

In June of 1774, Royal Gov. John Wentworth, fed up with the defiant general assembly, dissolved it. Doubling down on their defiance, assembly members formed a new Provincial Congress, unauthorized by the established government, then voted to send delegates (including Josiah Bartlett) to the new Continental Congress.

The social unrest escalated over the next year, and in August of 1775 Wentworth fled the state. With neither a governor nor a legal assembly, New Hampshire suddenly found itself without a government.

What to do?

This is a question seldom asked. Histories treat the writing of a new constitution as a natural and obvious decision. But there were other options.

Granite Staters could’ve embraced the anarchy. No government? No problem! But in the new constitution, they explained why the colony needed a civil government.

“The sudden and abrupt departure of his Excellency John Wentworth, Esq., our late Governor, and several of the Council, leaving us destitute of legislation, and no executive courts being open to punish criminal offenders; whereby the lives and properties of the honest people of this colony are liable to the machinations and evil designs of wicked men,” they wrote.

Anarchy out, they could’ve chosen tyranny. Or oligarchy. The wealthy and powerful could’ve filled the vacuum by sheer force. They could’ve declared themselves the provincial rulers, filled government offices with friends and cronies, and ruled like warlords.

But they didn’t. They were commoners, not noblemen. Steeped in Enlightenment ideas, they chose to create something different: a republic.

In the fall, the Provincial Congress asked the Continental Congress for guidance. New Hampshire Congressman Josiah Bartlett wrote back with the Congress’ advice to create an independent provincial government.

Meeting in December, the Provincial Congress hastily sketched out the framework of an independent government. But on whose authority?

Though neither the colony nor the Continental Congress had declared independence, the king was no longer considered a source of colonial authority. So how could they create a new government?

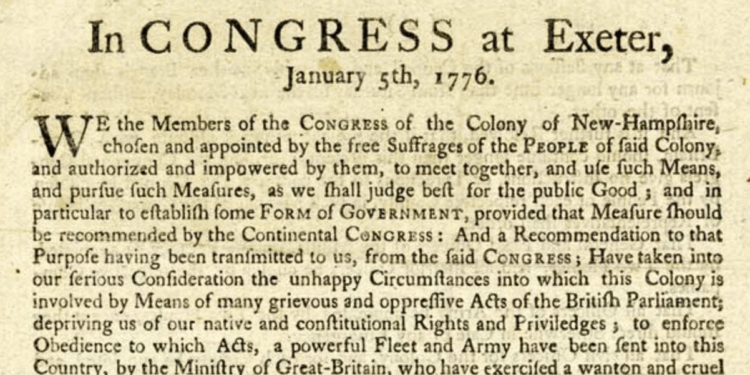

As they put it in the preamble to the constitution, they were “chosen and appointed by the free suffrages of the people…and authorized and empowered by them to meet together, and use such means and pursue such measures as we should judge best for the public good; and in particular to establish some form of government, provided that measure should be recommended by the Continental Congress.”

Rooting their authority in a dual mandate from the people and the Continental Congress (made up of representatives of the people), they established independence from the king without declaring it.

Deferring to Congress on the larger question of relations between the colonies and the crown, the Provincial Congress carefully avoided declaring the colony’s separation from Britain.

The new government was “to continue during the present unhappy and unnatural contest with Great Britain.”

Thus they ingeniously created a new government without overthrowing the old.

For that reason, New Hampshire’s 1776 constitution did not gain worldwide fame or popular historical notoriety. It isn’t popularly celebrated because it didn’t declare independence.

But what it did was tremendously significant. It created a new government on the authority of a sovereign people, not the king, and not parliament.

It was the colonies’ first independent government.

And although New Hampshire functions under a different constitution now, the 1776 constitution’s influence can still be felt. To this day, New Hampshire has a constitutionally weak governor, a legacy of the state’s experience under royal rule and its codification of that experience in 1776.

Granite Staters should be immensely proud to have created the first self-governing state of these United States—six months before the nation was created.

They should be proud too that the spirit of 76—a fierce sense of independence and a deep passion for self-determination—lives on in the state 250 years later.