Introduction

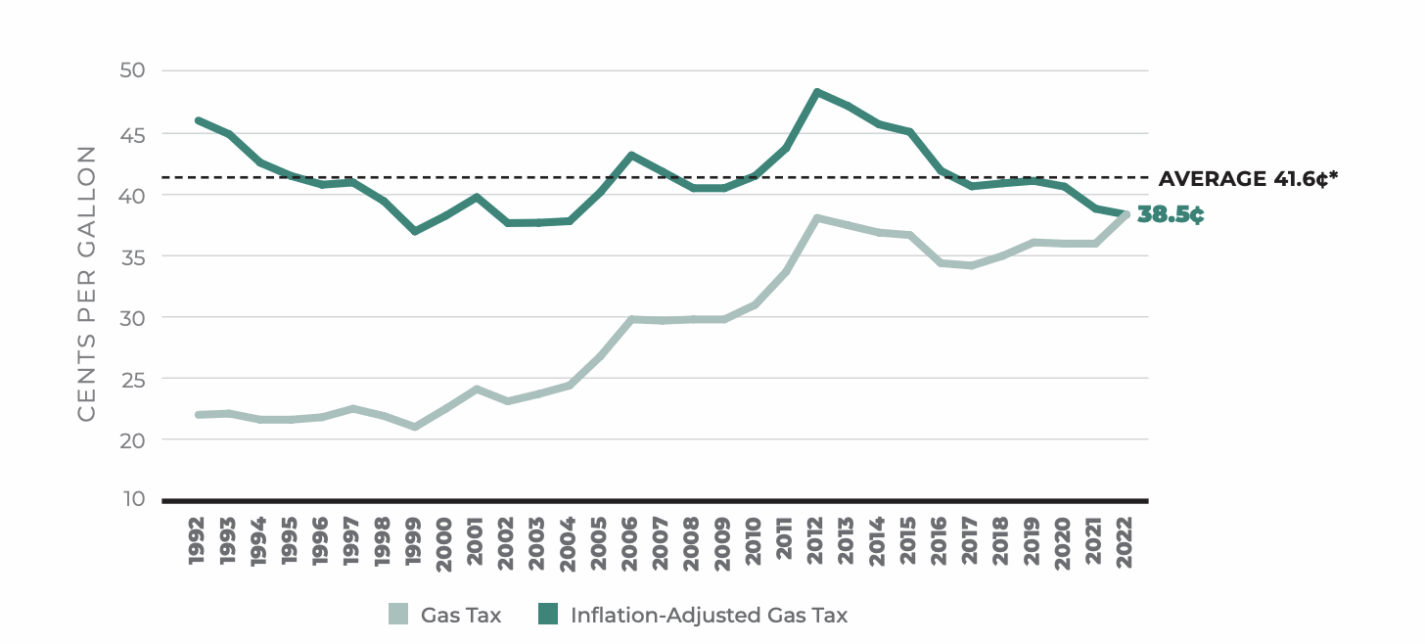

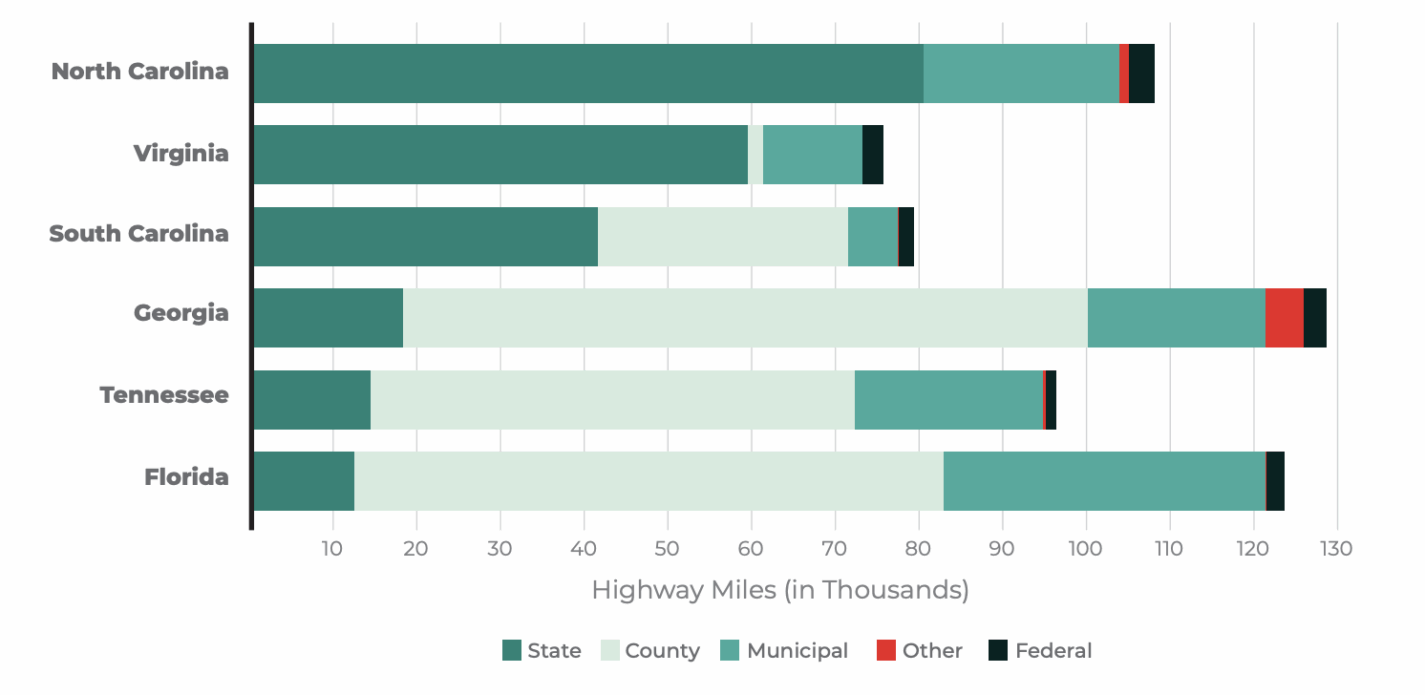

North Carolina has more than 80,000 miles of state-owned highways, more than any other state besides Texas. Unlike Texas, where state roads are one-fourth of the total 313,000 miles of roads in the state, North Carolina owns three-fourths of its 106,000 miles of roads.

In fact, North Carolina is one of only five states where the state government owns more than half of the road miles in the state. As a result, to build and maintain roads, its road network depends far more on user fees from the federal and state gas taxes, license fees, and vehicle sales tax than it does on local property taxes.

In addition, North Carolina has tried alternative funding mechanisms to supplement declining revenues from the motor fuels tax and other sources. The North Carolina Turnpike Authority manages tolls on the Triangle Expressway (new stretches of NC-147 and NC-540) in Durham and Wake counties. I-77 Mobility Partners won a 50-year contract to partner with the Department of Transportation (NCDOT) on I-77 express lanes in Charlotte. North Carolina uses Grant Anticipation Revenue Vehicle (GARVEE) financing to spend future federal funds today. In 2018, the General Assembly approved up to $300 million in new Build NC borrowing per year, over 10 years, to fund additional road construction.

In 2017, North Carolina created the State Capital and Infrastructure Fund (SCIF), which is used to fund capital and infrastructure projects on a pay-as-you-go basis, rather than through debt financing.

According to a 2013 study by transportation experts at the Hartgen Group and the Reason Foundation, better prioritization of projects could allow North Carolina to meet its highway needs without additional taxes. Efficient spending is critical because roads are only as valuable as the economic activity they make possible. Without productive activity, they are simply liabilities in need of maintenance.

The Strategic Transportation Investments formula, approved in legislation in 2013, replaced much of the political wrangling that had marked transportation planning in the past with a data-driven approach. While improvements are needed to calculate the total cost and congestion savings for each project, the formula will help North Carolina meet anticipated transportation needs.

NCDOT’s latest initiatives to prepare for the future include the 2020 report entitled “NC Moves,” which attempts to outline transportation needs, and a 2021 report by NC FIRST (Future Investment Resources for Sustainable Transportation), which provides recommendations for how to fund those plans.

A 2021 report written by transportation expert Randal O’Toole and released by the John Locke Foundation described the NC Moves report as “less of a plan than part of a media campaign,” while criticizing the NC FIRST report as a document that outlined wants rather than needs. O’Toole’s recommendations for improving the funding and focus of North Carolina’s transportation system are included in part below.

Key Facts

- North Carolina state government dedicates roughly 78% of the $5 billion in current annual transportation spending – which includes $1.3 billion in federal funds to building and maintaining more than 80,000 miles of roads and more than 13,500 bridges. Municipalities add another $800 million for local roads and transportation needs. North Carolina has no county-owned roads.

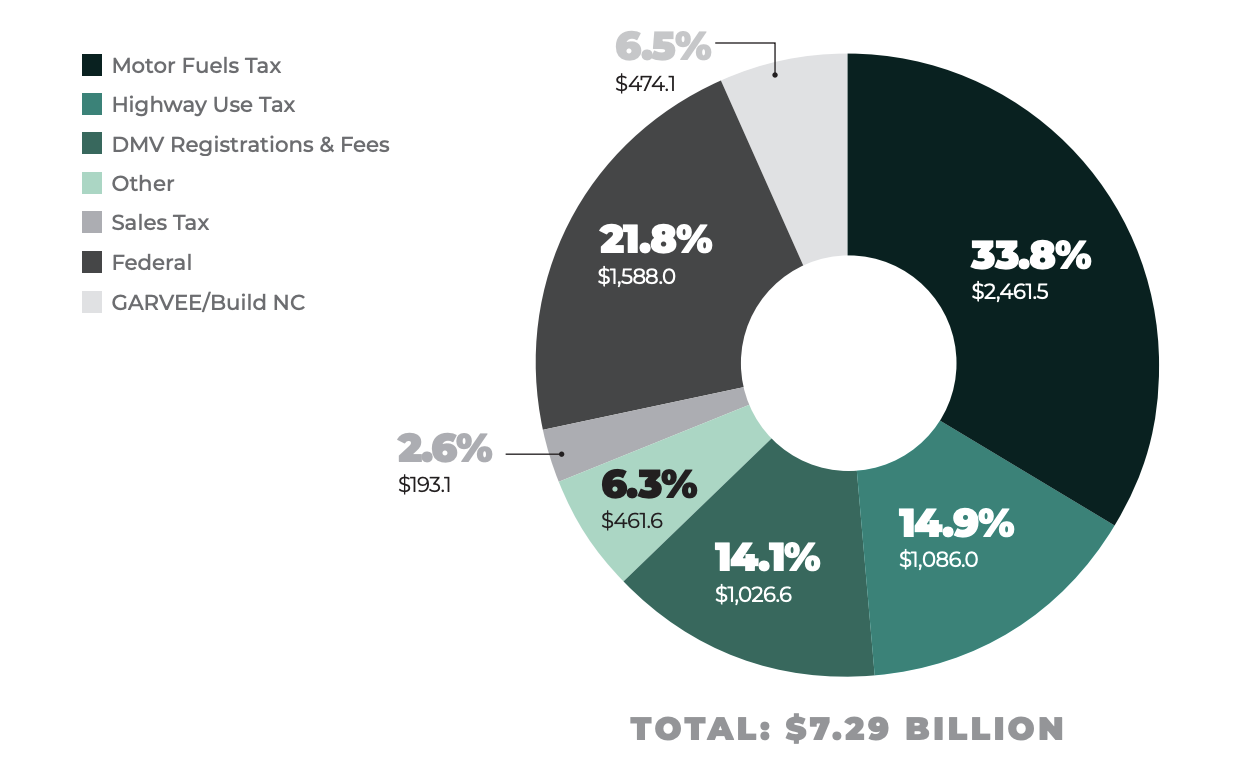

- Because of the proliferation of more fuel-efficient vehicles, including an increase in electric vehicles, raising revenue from the motor fuels tax to pay for roads will remain a challenge. The current gas tax rate of 38.5 cents (as of the end of 2022) comes in a little shy of the inflation-adjusted 41.6-cent average over the past 30 years.

- Although North Carolinians think more funding is needed, they do not necessarily support new taxes. A March 2016 poll from High Point University found that 57% of respondents opposed toll roads, 68% opposed increasing the gas tax, and 84% opposed taxing motorists per mile traveled.

Recommendations

1. Improve the Strategic Transportation Investment Plan (STIP) formula to include total lifetime cost and anticipated congestion improvements.

The STIP is a marked improvement over previous road-funding decisions that were heavily influenced by political considerations, but it can still be improved. Costs to the community may be understated in the current formula.

2. Prepare for future road funding to shift away from the gas tax.

The gas tax has been a convenient and effective user fee, but fuel-economy improvements combined with a growing market share for electric vehicles make it a questionable source of future road funds. Prominent among future financing options would be shifting from the gas tax to a charge based on vehicle miles and weight, a separate fee for hybrids/EVs, or a property tax to pay for more locally owned and maintained roads. Impact fees may be another option but have had a mixed record when implemented.

3. Stop Using Highway User Fees for Non-Highway or Road Purposes.

Diverting gas tax and vehicle registration fees for airports or public transportation like Amtrak or light rail is a poor use of funds and often burdens low-income households to benefit items more commonly used by higher-income people.

4. Invest More in Safety and Maintenance.

The condition of state collector roads and arterials are declining, suggesting the need for more maintenance. Meanwhile, some highways are more dangerous than others, but NCDOT seems to have little interest in understanding why or addressing the problem.

5. Consider Ways to Capture the Value Created by Roads for Property and Business Owners.

Municipalities are responsible for few roads in North Carolina, and counties are responsible for none. As a result, property tax, which could capture the value created by proximity to the transportation network, is not available to pay for most roads. Public/private partnerships could also open new ways to purchase and develop land near the right-of-way.

6. Develop a Plan for “Orphan Roads.”

In 2023, the Locke Foundation published a report examining the issue of “orphan roads.” These are roads for which there is no clear owner. Typically, orphan roads are located outside of incorporated areas and are not maintained by local or state government.

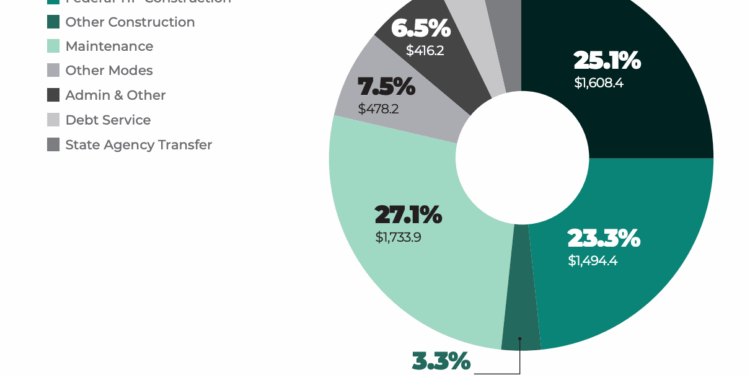

Transportation Spending, FY 2022-23 (in millions)

Source: NC Department of Transportation

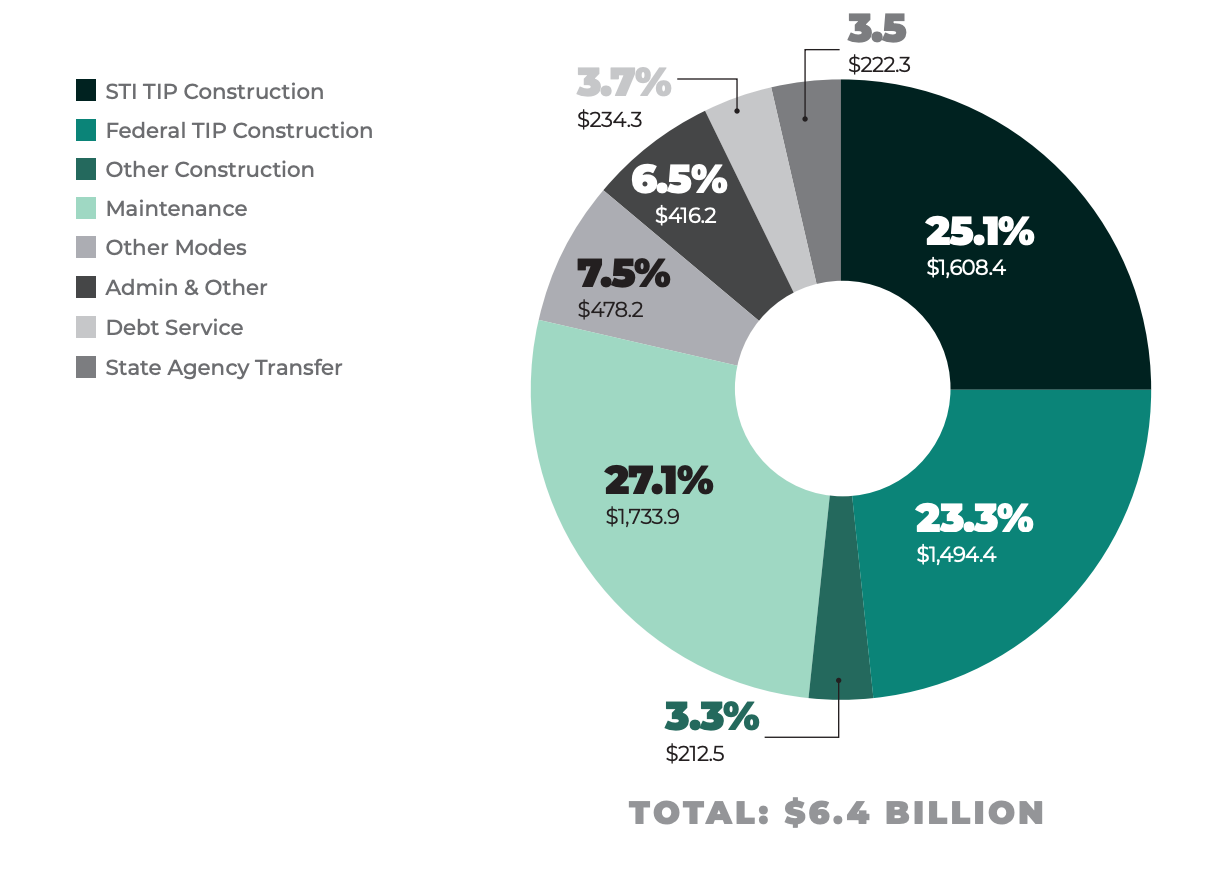

Sources of Transportation Funding, FY 2022-23 (in millions)

Source: NC Department of Transportation

Notes: *”other” includes “other federal agencies & grants” plus “other“

North Carolina Gas Tax Over Three Decades

Notes: *adjusted for inflation

Source: NC Department of Transportation

North Carolina State-Funded Roads Comprise 75% of Public Roads

Source: US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration