A staggering £1.2 trillion. That’s what it took to rescue Britain’s banks in 2008 – £133 billion in hard cash and over a trillion more in guarantees and non-cash support, according to the National Audit Office. Most of those guarantees were never drawn upon. But the damage was done. Confidence in the financial system collapsed. Trust in the state’s ability to manage the economy evaporated.

We were told, never again.

Never again would any single institution be allowed to grow so large, so deeply embedded, that its failure would threaten the country’s stability.

Yet here we are in 2025. The new ‘too big to fail’ isn’t a bank or a hedge fund. It’s the British state.

Overgrown, overcentralised and shielded by a dense canopy of entitlements, public sector unions, quangos and bureaucracy, the modern state now poses a systemic threat to the UK’s long-term solvency. It doesn’t just dominate national life. It distorts it. And unlike the banks, there is no resolution mechanism, no restructuring plan and, crucially, no political will to confront the scale of the crisis.

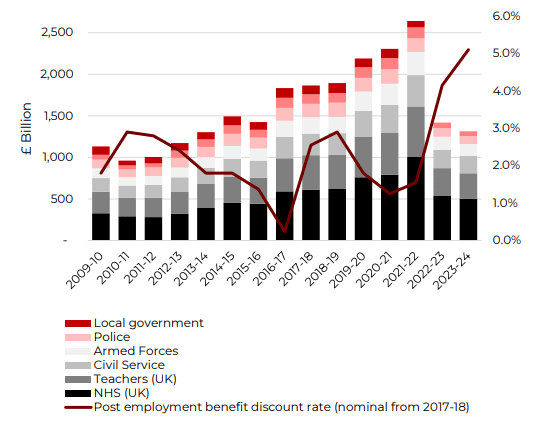

The numbers speak for themselves. In 2021-22, Britain’s unfunded public sector pension liabilities reached £2.64tn – more than double the cost of the bank rescue and equivalent to 107% of GDP. Since then, rising bond yields (and thus higher discount rates) have brought the figure down to £1.3tn. But this is no cause for celebration. These are not asset-backed pensions. They are defined benefit promises: gold-plated retirement incomes underwritten by taxpayers, with no capital base beyond future tax revenues.

The public sector, in effect, plays both borrower and lender to the state. Its employees, from teachers and police officers to civil servants and NHS staff, are among the government’s largest and most politically protected creditors.

Nigel Farage has described the system as ‘a Ponzi scheme’ and ‘the single biggest ticking bomb in our government finances’. The language may be emotive, but the underlying concern is real.

15-Year Trend of Net Liabilities of Public Sector Pension Schemes

Source: HMT, WGA y/e 31 March 2024

Meanwhile, millions in the private sector have seen their pensions diluted or replaced entirely. Final salary schemes have largely disappeared. In their place are defined contribution pensions, with no guarantees, no state backing and full exposure to market risks. The gap between public and private retirement provision is not just unsustainable, it is fundamentally unfair.

That £1.3tn pension liability sits on top of £1.2tn in public spending last year, roughly 45% of GDP. The OBR expects spending to rise to £1.28tn this year, with long-term forecasts pointing to 60% of GDP within decades unless serious reform is undertaken.

If a City firm posted numbers like these, they’d spark panic. In Whitehall, they barely raise an eyebrow. To challenge them is to confront the forces that sustain Britain’s political establishment: the unions, the civil service and the sprawling administrative state. So, the Government’s response is the same: more borrowing, more taxation and more denial. As I argued recently, this isn’t fiscal realism. It’s fantasy economics.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the NHS. In 2023–24, NHS England spent £188.5bn. By 2028-29, that figure is expected to climb to £247bn. And what has that bought? Nearly 7.5 million people stuck on waiting lists. Productivity still almost 9% below pre-pandemic levels. Junior doctors striking again for another eye-watering inflation-linked pay rise, calculated using a dubious RPI-based metric, despite having already received a 28.9% increase over the last three years. (The TaxPayers’ Alliance has more on this flawed arithmetic here.) One six-day walkout alone cancelled 113,000 appointments. Overall, more than 1.2m procedures have been disrupted.

The NHS now employs 2.06m people, including 1.37m full-time equivalent roles, (excluding GPs). Half the budget goes on staff costs. Another £10bn is spent annually on administration once trusts are included. Yet we’re told the whole system is on the brink of collapse unless more money is poured in.

The problem is not funding. It is structural. And fixing that would take political courage.

Sound familiar?

The same story plays out across government. Public sector employment has hit 6.15m. Central government jobs – including the NHS – are at a record 4.02m, up 93,000 in a single year. The civil service alone has swelled by over 100,000 since 2016, now exceeding 550,000. Meanwhile, local government employment has fallen to ‘just’ 1.98m.

And what has all this growth delivered? ‘We haven’t seen a commensurate increase in measured public sector output,’ Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey recently observed.

Flagship infrastructure projects like HS2, school rebuilds and the New Hospital Programme have become multi-billion-pound money pits with no clear outcomes. Each stands as a monument to dysfunction, endlessly recycled through taskforces and strategic reviews. This isn’t a growth agenda. It’s paralysis.

And while the machine falters, the Treasury reaches for stealth. By freezing thresholds and allowances, it quietly drags millions more into higher tax bands each year. Some families now face marginal rates exceeding 60% once child benefit tapers and student loan repayments are added. The result? A tax burden at multi-decade highs.

Let’s stop pretending. Britons are not paying more tax for better services. They’re paying to feed a bloated apparatus that exists primarily to serve itself, an apparatus that rejects reform, shields failure and seems to punish innovation.

The Conservative Party had fourteen years to fix this. It talked tough. It promised a bonfire of the quangos. But it bottled it. Instead, it presided over the biggest expansion of the state since World War II. Covid may have accelerated the trend. The unwillingness to confront vested interests predates it.

Britain doesn’t need more tweaks. It needs a rethink from first principles. What is the state for? What should it deliver? Where should it step back? Stop measuring success by what’s spent. Start measuring it by what gets done.

This doesn’t mean cuts for their own sake. It means restoring democratic control. Margaret Thatcher understood that in the 1980s. Her reforms weren’t just about privatisation or deregulation. They reasserted the principle that the state exists to serve citizens, not the other way around. She tackled inefficiency. She challenged union power. She delivered a reset.

That’s what we need now.

The state isn’t too big to fail. It’s too big to manage. If we keep avoiding reform and spinning failure as success, the next crisis won’t be a sudden crash like 2008. It’ll be a slow, grinding collapse, robbing our children of prosperity and our democracy of trust.

Britain needs a government with the courage to confront the state, not just administer it. That means bold reform, not bureaucratic tinkering. Radical honesty, not endless reviews. And action – now, not after the next election.

– the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.

Columns are the author’s own opinion and do not necessarily reflect the views of CapX.