The plaintiffs were destined to lose Pierce v NC State Board of Elections, a racial gerrymandering claim against state Senate districts in northeastern North Carolina. They not only failed to prove that the districts were racial gerrymanders, but the evidence presented in the case may help pave the way for the General Assembly to redraw the First Congressional District to lean Republican.

A weak case out of limited options

A pair of cases closed the door on claims of political gerrymandering. Both the United States Supreme Court (Rucho v. Common Cause, 2019) and the North Carolina Supreme Court (Harper v. Hall, 2023) found that “claims of partisan gerrymandering present nonjusticiable, political questions.”

While there are still limits to what the General Assembly can do when drawing districts, those two rulings left only one line of attack for redistricting lawsuits:

The other common avenue for redistricting lawsuits is based on claims of racial gerrymandering in violation of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) or the Equal Protection clause of the [Fourteenth] Amendment.

However, there are no obvious avenues of attack on that front either. Pierce v. NC State Board of Elections focuses on state senate districts in the so-called “Black Belt” region of majority-black counties in northeastern North Carolina. That area comes the closest to meeting the “Gingles test” of criteria plaintiffs must meet to prove racial gerrymandering claims under the VRA. [The plaintiffs increased their number of “demonstration districts” to four by the time of the trial in early 2025.]

While we will provide a fuller analysis of Pierce v. NC State Board of Elections later, a look at the complaint reveals that both of the plaintiff’s proposed remedial maps use race as the predominant factor in drawing districts, which violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Cooper v. Harris, 2017).

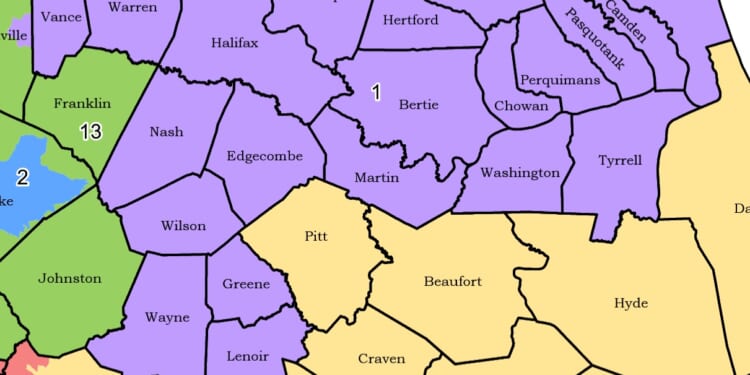

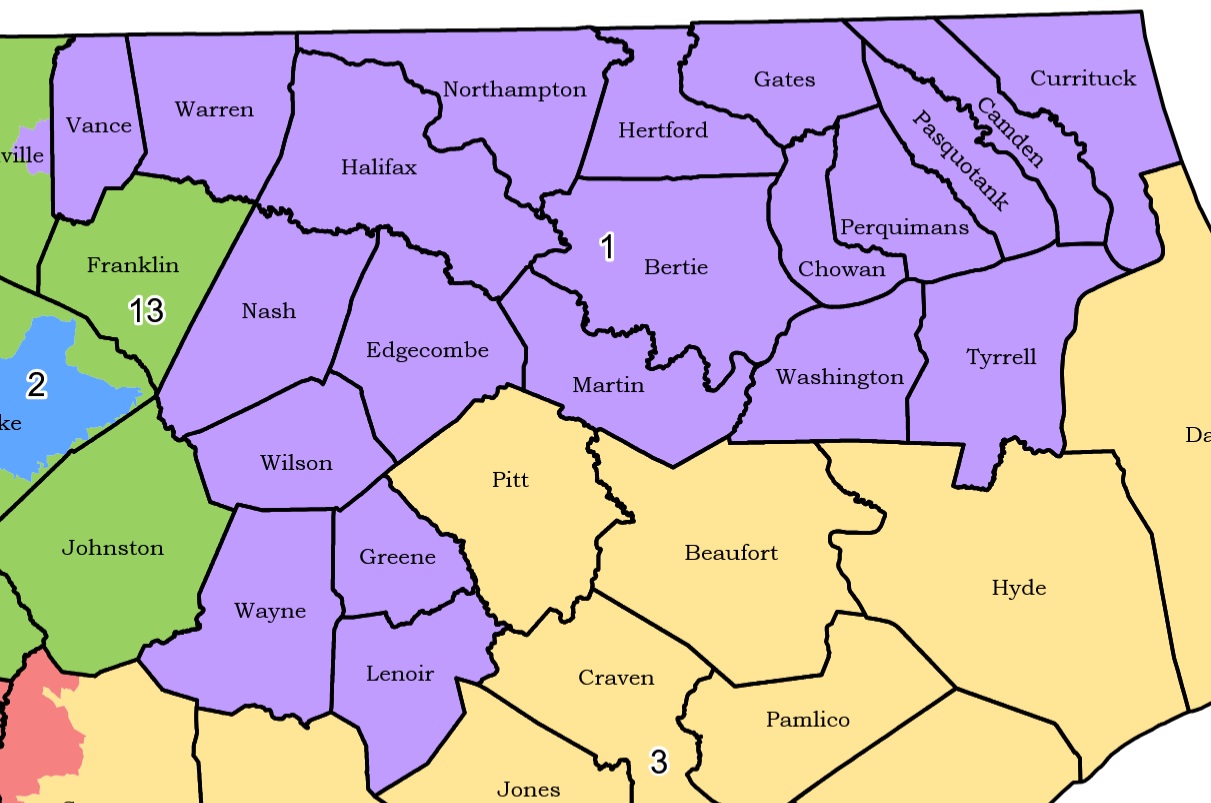

Pierce focused on two state Senate districts in the Northeastern corner of the state. We never got around to doing a fuller analysis of Pierce v. NC State Board of Elections, partly because we believed that the case was too weak to warrant further analysis.

Federal court found no Voting Rights Act violation in Senate districts

Now, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina has agreed, ruling that “plaintiffs failed to prove that [the State Board of Elections and legislative defendants] violated Section 2 of the VRA.”

The court also noted that the legislative maps the General Assembly passed in 2023 did not reduce Black representation below what you would expect based on their proportion of the population:

[O]n November 5, 2024, North Carolina voters voted in the Senate and House districts created in these maps without racial data and elected 10 out of 50 African-American Senators (i.e., 20% of the Senate) and 28 out of 120 African-American Representatives (i.e., 23.3% of the House). Thus, African-American legislators in North Carolina hold 21.7% of the legislative seats. These numbers approximate or exceed North Carolina’s African-American voting age population of 21.37% and its African-American population of 22%.

The US Supreme Court established the “Gingles test,” a three-part evaluation of possible racial gerrymanders in Thornberg v. Gingles. The district court found in Pierce that plaintiffs satisfied the second test (that Black voters in the area are “politically cohesive”), but failed to prove the first (that you can draw a compact and “reasonably configured” district with a majority Black population) and third (that White voters vote sufficiently as a block to “defeat the minority’s preferred candidate”) tests.

Even if the plaintiffs had satisfied all three of the Gingles tests, they would have also had to “go on to prove that, under the totality of the circumstances, the district lines dilute the votes of the members of the minority group.” That is done by reviewing what is known as “Senate factors.” While over a third of the 126-page decision is spent on a review of those factors and related analyses, the bottom line was the court found that race was not the predominant factor in drawing the districts in question:

The evidence shows North Carolina (including northeast North Carolina) as a place “where racial animosity is absent although the interest of racial groups diverge” and that politics-not race-explain the voting patterns.

So, other than demonstrating that Black North Carolinians tend to vote as a block, the plaintiffs failed to prove any of the points they claimed showed that the state Senate districts were racial gerrymanders.

Is the door open for redrawing the First Congressional District?

There are rumors that North Carolina is about to join the mid-decade redistricting war kicked off by Texas and California. The most likely target is the First District, currently represented by Democrat Rep. Don Davis.

There is little doubt that any redrawing of that district will invite a lawsuit on racial gerrymandering groups. The First has traditionally been one of two “Black districts” in the state, the other being the 12th District in Charlotte. The ruling in Pierce, along with a 2024 Supreme Court ruling on a South Carolina racial gerrymandering claim, shows legislators how they can do that without running afoul of the Voting Rights Act.

They have to demonstrate that the districts is “reasonably configured” and that partisanship, not race, was the motivating factor in redrawing it.

Quoting Allen v. Milligan (2023), the court wrote in Pierce v NC State Board of Elections that “[T]entacles, appendages, bizarre shapes, or any other obvious irregularities’ are strong indicators that a district is not reasonably configured.” The current First District is reasonably compact, with a Reock compactness score of 0.42 and a Polsby–Popper score of 0.29. It only splits one county. So, the new district should be similarly compact and also split only one county. Accomplishing that while maintaining equal population between districts would be difficult and require changes to at least three districts (the First, Third, and Thirteenth).

Showing that partisanship, rather than race, drove redistricting decisions might be easier. The first step is not to use racial data when drawing districts. The court considered the lack of racial data when drawing state Senate districts a factor in favor of defendants in Pierce. The court also noted that there is a “difference between being aware of racial considerations and being motivated by them.” Republicans could help their cause if post-redistricting analysis found that the district is significantly less Democratic while losing comparatively fewer Black voters.

Consider redistricting reform for 2031

While they are under the hood, legislators should consider redistricting reform to ban the use of any political or racial data and to more strictly follow traditional criteria such as compactness and keeping political communities whole. The reforms could be implemented starting with the 2031 round of redistricting. You can find details of those reforms in the John Locke Foundation report Limiting Gerrymandering in North Carolina.